Included:

Learning Machine Learning from scratch, hardware options, finding

mentorship, who’s important to know in the field, freelancing as a

machine learning engineer, concepts that make you difficult to replace,

preparing for interviews, interviewing with big silicon valley tech

companies, adopting the best productivity habits, and a few other

things.

Credentials:

I graduated with a degree in molecular biology and worked in biotech

after college. Within a year of leaving that industry, I was working

with the Tensorflow team at Google on probabilistic programming tools. I

later joined a security startup as a machine learning engineer.

Disclaimer:

Much of this is based on my own experience, peppered with insights from

friends of mine who have been in similar boats. Your experience might

not be identical. The main value is giving you a roadmap of the space so

you can navigate it if you have no idea what you’re doing. If you have

your own methods for learning ML that are working better than the ones

listed here (like, if you’re literally in school learning about this

stuff), keep on using them.

In

a span of about one year year, I went from quitting biomedical research

to becoming a paid Machine Learning Engineer, all without having a

degree in CS or Math. I’ve worked on side-projects that have been shared

with tens of thousands on Twitter, worked with startups in facial

recognition and distributed apps, sold a side-project, and even worked

with Google’s Tensorflow Team on new additions to Tensorflow. Again,

this was all without having a computer science degree.

This

post, while long, is a compilation of all the important concepts, tips,

and resources for getting into a machine learning career. From readers

who are not yet in College, to readers who have been out of college for a

while and are looking to make a switch, I’ve tried to distil the most

generally applicable points from my own journey that would be beneficial

to a wide array of people.

Enjoy.

Part 1: Introductions, Motivations, and Roadmap

Part 2: Skills of a (Marketable) Machine Learning Engineer

Part 3: Immersion and Finding Mentors

Part 4: Software and Hardware Resources

Part 5: Reading Research Papers (and a few that everyone should know)

Part 6: Groups and People you should be Familiar with

Part 7: Problem-Solving Approaches and Workflows

Part 8: Building your portfolio

Part 9: Freelancing as an ML developer

Part 10: Interviewing for Full-time Machine Learning Engineer Positions

Part 11: Career trajectory and future steps

Part 12: Habits for Improved Productivity & Learning

Part 1: Introductions, Motivations, and Roadmap

Introductions

If you’ve been following the news at all, chances are you’ve seen the headlines about how much demand there is for machine learning talent. In the recent LinkedIn Economic Graph

report, “Machine Learning Engineer” and “Data Scientist” were the two

fastest growing jobs of 2018 (9.8x and 6.5x growth, respectively).

Medium itself is rife with example projects, tutorials, reviews of software, and tales of interesting applications.

Despite the apparent demand, there seem to be few resources on actually

entering this field as an outsider, as compared the resources available

for other areas of software engineering. That’s why I’m writing this

mega-post: to serve as condensed resource for the lessons of my journey

to becoming a Machine Learning Engineer from a non-CS background.

“But Matt”, you must be saying, “That’s not at all unusual, lots of people go into machine learning from other fields.”

It’s

true that many non-CS majors go into the field. However, I was not a

declared statistics, mathematics, physics, or electrical engineering

major in college. My background is in molecular biology, which some of

you may have noticed is frequently omitted from lists of examples of

STEM fields.

While

I was slightly more focused on statistics and programming during my

undergrad than most bio majors, this is still an unusual path compared

to a physicist entering the field (as this lovely post from Nathan Yau’s FlowingData illustrates).

Backstory

I

don’t think it’s wise to focus too much on narratives (outside of

preparing for interviews, which we will get to). There’s many ways I

could spin a narrative for my first steps into the machine learning

field, both heroic and anti-heroic, so here’s one of the more common

ones I use:

Since

high school, I had an almost single-minded obsession with diseases of

aging. A lot of my introduction to machine learning was during my

undergraduate research in this area. This was in a lab that was fitting

discrete fruit fly death data to continuous equations like gompertz and

weibull distributions, as well as using image-tracking to measure the

amounts of physical activity of said fruit flies. Outside of this

research, I was working on projects like a Google Scholar scraper to

expedite the search for papers for literature reviews. Machine learning

seemed like just another useful tool at the time for applying to

biomedical research. Like everyone else, I eventually realized that this

was going to become much bigger, an integral technology of everyday

life in the coming decade. I knew I had to get serious about becoming as

skilled as I could in this area.

But why switch away from aging completely?

To answer that, I’d like to bring up a presentation I saw by Dr. David

Sinclair from Harvard Medical School. Before getting to talking about

his lab’s exciting research developments, he described a common struggle

in the field of aging. Many labs are focused on narrow aspects of the

process, whether it be specific enzyme activity, nutrient signalling,

genetic changes, or any of the other countless areas. Dr. Sinclair

brought up the analogy of the blind men and the elephant, with respect

to many researchers looking at narrow aspects of aging, without spending

as much time recognizing how different the whole is from the part. I

felt like the reality was slightly different (that it was more like

sighted people trying identify an elephant in the dark while using laser

pointers instead of flashlights), but the conclusion was still spot-on:

we need better tools and approaches to addressing problems like aging.

This,

along with several other factors, made me realize that using the

wet-lab approach to the biological sciences alone was incredibly

inefficient. Much of the low-hanging fruit in the search space of cures

and treatments has been acquired long ago. The challenges that remain

encompass diseases and conditions that might require troves of data to

even diagnose, let alone treat (e.g., genomically diverse cancers,

rapidly mutating viruses like HIV). Yes, I agree with many others that aging is definitely a disease, but it is also a nebulously defined one that affects people in wildly varying ways.

I

decided that if I was going to make a large contribution to this, or

any other field I decided to go into, the most productive approach would

be working on the tools for augmenting and automating data analysis. At

least for the near future, I had to focus on making sure my foundation

in Machine Learning was solid before I could return my focus to specific

cases like aging.

“So…what exactly is this long-a** post about again?”

There

are plenty of listicles and video tutorials for specific machine

learning techniques, but there isn’t quite the same level of

career-guide-style support like there is for web or mobile developers.

That’s why this is more than just compiling lists of resources I have

turned to for studying. I also tried to document the best practices I’ve

found for creating portfolio projects, finding both short-term and

long-term work in the field, and keeping up with the rapidly-changing

research landscape. I will also compile nuggets of wisdom from others I

have interviewed who are further along this path than I am.

The level of technical ability you need to show is not lowered, it’s even higher when you don’t have the educational background, but it’s totally possible.

— Dario Amodei, PhD, Researcher at OpenAI, on entering the field without a doctorate in machine learning

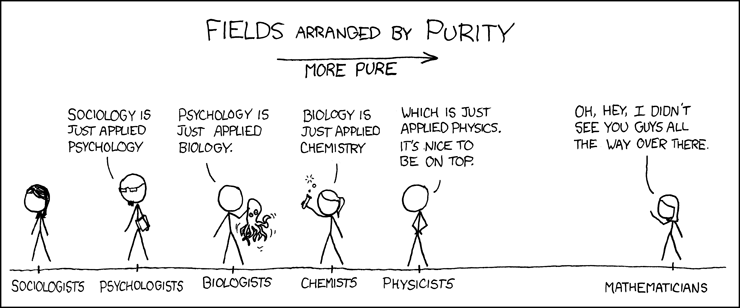

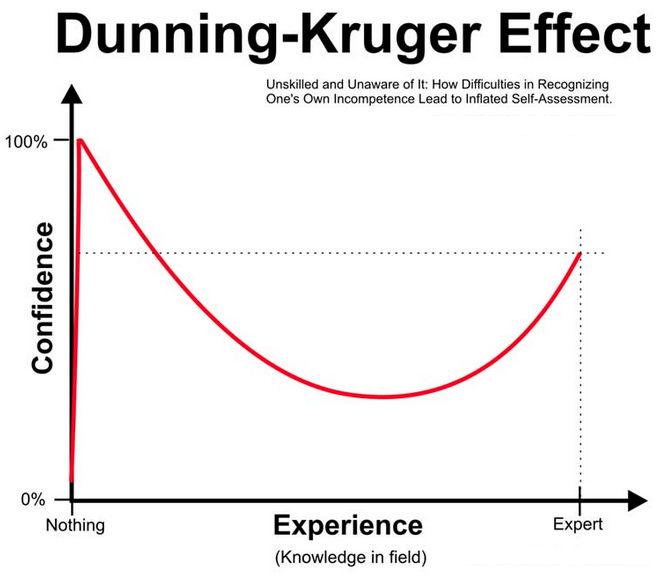

Ultimately,

I want whoever reads this to get a detailed map of the space, so if

they decide to go down my path, they can get through the valley of the

Dunning-Kruger effect much more quickly.

With

that in mind, we’ll start with a rough overview of the skills needed to

master in order to become an (employable) machine learning engineer:

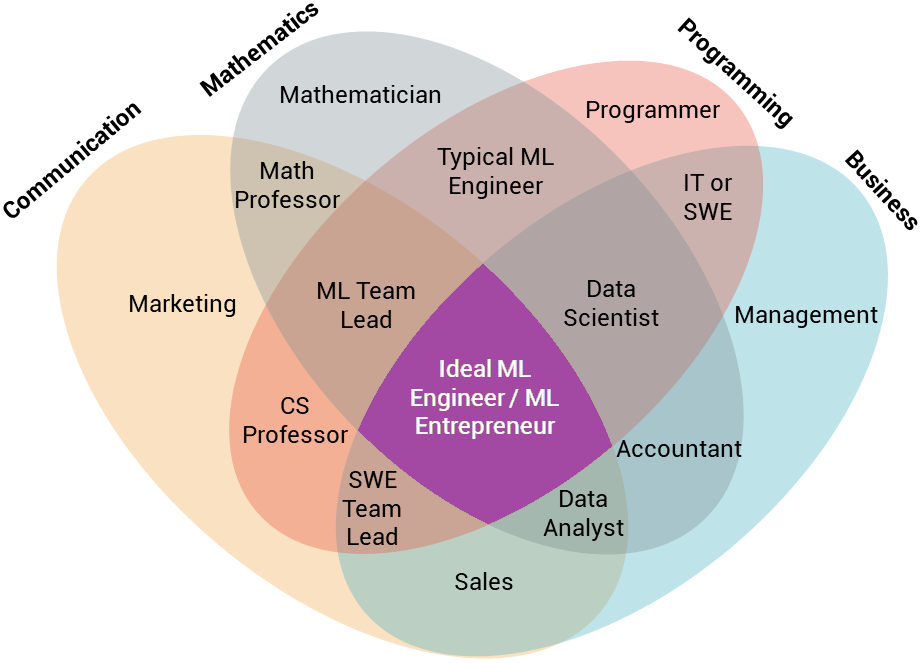

Part 2: Skills of a (Marketable) Machine Learning Engineer

Becoming

a machine learning engineer still isn’t quite as straightforward as

becoming a web or mobile engineer, as we discussed in the

previous section. This is despite all of the new programs geared toward

machine learning both inside and outside of traditional schools. If you

ask many people with the title of “Machine Learning Engineer” what they

do, you’ll often get wildly different answers.

The goal of this section is to help you put together the beginnings of a mental semantic tree (Khan Academy’s example of such a tree) for learning machine learning (à la Elon Musk’s now famous method).

Based on my own experiences, as well as reaching out to hundreds of

machine learning engineers in both academia and industry, here’s an

overview of the soft skills, basic technical skills, and more

specialized skills you’ll need.

Soft Skills

We

need to cover a few non-technical skills that you should keep in mind

before diving into the deep end. Yes, machine learning is mainly math

and computer science knowledge. However, you’ll most likely need to find

ways of applying this to solve real problems.

Learning new skills:

The field is rapidly changing. Every month new neural network models

come out that outperform previous architecture. GPU-manufacturers are in

an arms race. 2017 saw just about every major tech giant release their own machine learning frameworks.

There’s a lot to keep up with, but luckily the ability to quickly learn

things is something you can improve on (Growth mindsets for the win!).

Classes like Coursera Learning how to Learn are great for this. If you have Dyslexia, ADD, or anything similar, the Speechify app

can offer a bit of a productivity boost (this is one app that I used a

bunch to make as much use of my time reading and re-reading papers).

Muad’Dib learned rapidly because his first training was in how to learn. And the first lesson of all was the basic trust that he could learn. It’s shocking to find how many people do not believe they can learn, and how many more believe learning to be difficult. Muad’Dib knew that every experience carries its lesson.

- Dune, by Frank Herbert

Time-management: A lot of my friends have gone to Ivy League schools like Brown, Harvard, and MIT. Out

of the ones that made it there and continued to succeed afterwards, it

seemed that skill in time management was a much bigger factor in their

success than any natural talent or innate intellect. The same pattern

will likely apply to you. When it comes to a cognitively-demanding

task like learning machine learning, RESIST THE URGE TO MULTI-TASK. Yes,

at some point you may need to run model-trainings in parallel if you

have the compute resources, but you should put your phone on airplane

mode when studying and avoid doing multiple tasks at the same time. I

cannot recommend highly enough Cal Newport’s book “Deep Work” (or his Study Hacks Blog). If you’re still in college or high school, Jessica Pointing’s Optimize Guide is also a great resource. I’ll go into more resources like this in the next post in this series.

Business/Domain knowledge:

The most successful machine learning projects out there are going to be

those that address real pain points. It will be up to you to make sure

your project is not the machine learning equivalent of Juicero.

In academia, the emphasis is more on the side of improving metrics of

algorithms. In industry, the focus is all about making those

improvements count towards solving customer or company problems. Beyond

taking classes in entrepreneurship while you’re in school, there are

plenty of classes online that can also help (Coursera has a pretty decent selection). If you want a more comprehensive overview, you can try the Smartly MBA.

It’s creators impose an artificially low acceptance rate, but if you

get in it’s free. At the very least, business or domain knowledge helps a lot with feature engineering (many of the top-ranking Kaggle teams often have at least one member whose role it is to focus on feature engineering).

Communication:

You’ll need to explain ML concepts to people with little to no

expertise in the field. Chances are you’ll need to work with a team of

engineers, as well as many other teams. Oh, and you’ll need to get past

the dreaded interviews eventually. Communication is going to make all of

this much easier. If you’re still in school, I recommend taking at

least one course in rhetoric, acting, or speech. If you’re out of

school, I can personally attest to the usefulness of Toastmasters International.

Rapid Prototyping:

Iterating on ideas as quickly as possible is mandatory for finding one

that works. Throughout your learning process you should maximize the

amount of new, useful, and actionable information you are getting. In

machine learning, this applies to everything from picking the right

model, to working on projects such as A/B testing. I had the pleasure of

learning a lot about rapid prototyping from one of Tom Chi’s

prototyping workshops (he’s the former Head of Experience at GoogleX,

and he now has an online class version of his workshop). Udacity also has a great free class on rapid prototyping that I highly recommend.

Okay,

now that we’ve got the soft skills out of the way, let’s get to the

technical checklist you were most likely looking for when you first

clicked on this article.

The Basic Technical Skills

Python (at least intermediate level) — Python

is the lingua franca of Machine Learning. You may have had exposure to

Python even if you weren’t previously in a programming or CS-related

field (it’s commonly used across the STEM fields and is easy to

self-teach). However, it’s important to have a solid understanding of

classes and data structures (this will be the main focus of most coding

interviews). MITx’s Introduction to Computer Science

is a great place to start, or fill in any gaps. In addition to

intermediate Python, I also recommend familiarizing yourself with

libraries like Scikit-learn, Tensorflow (or Keras if you’re a beginner), and PyTorch, as well as how to use Jupyter notebooks.

C++ (at least intermediate level) — Sometimes

Python won’t be enough. Often you’ll encounter projects that need to

leverage hardware for speed improvements. Make sure you’re familiar with

basic algorithms, as well as classes, memory management, and linking.

If you also choose to do any machine learning involving Unity, knowing C++ will make learning C# much easier.

At the very least, having decent knowledge of a statically-typed

language like C++ will really help with interviews. Even if you’re

mostly using Python, understanding C++ will make using

performance-boosting Python libraries like Numba a lot easier. Learn C++ has been one of my favorite resources. I would also recommend Programming: Principles and Practice Using C++ by Bjarne Stroustrup.

Once you have the basics of either Python or C++ down, I would recommend checking out Leetcode or HackerRank

for algorithm practice. Quickly solving basic algorithms is kind of

like lifting weights. If you do a lot of manual labor (e.g., programming

by day), you might not necessarily be lifting a lot of weights. But, if

you can lift weights well, most people won’t doubt that you can do

manual labor.

Onward to the math…

Linear Algebra (at least basic level) — You’ll

need to be intimately familiar with matrices, vectors, and matrix

multiplication. Khan Academy has some good exercises for linear algebra. I also recommend 3blue1brown’s YouTube series Essence of Linear Algebra for getting a better intuition for linear algebra. As for textbooks, I would recommend Linear Algebra and Its Applications by Strang & Gilbert (for getting started), Applied Linear Algebra by B. Noble & J.W. Daniel (for applied linear algebra), and Linear Algebra, Graduate Texts in Mathematics by Werner H. Greub (for more advanced theoretical aspects).

Calculus (at least basic level) — If

you have an understanding of derivatives and integrals, you should be

in the clear. Otherwise even simpler concepts like gradient descent will

elude you. If you need more practice, Khan Academy is likely the best

source of online practice problems out there for differential, integral, and multivariable calculus. Differential equations are also helpful for machine learning.

Statistics (at least basic level) — Statistics

is going to come up a lot. At least make sure you’re familiar with

Gaussian distributions, means, and standard deviations. Every bit of

statistical understanding beyond this helps. Some good resources on

statistics can be found at, you probably guessed it, Khan Academy. Elements of Statistical Learning, by Hastie, Tibshirani, & Friedman, is also great if you’re looking for applications of statistics to machine learning.

BONUS: Physics (at least basic level) — You

might be in a situation where you’d like to apply machine learning

techniques to systems that will interact with the real world. Having

some knowledge of physics will take you very far, especially when it

comes to understanding concepts like Nesterov momentum or energy-based models. For learning physics online, I would point to Physics for the 21st Century, MIT’s online physics courses, UC Berkeley’s Physics for Future Presidents, and Khan Academy. For textbooks, I would look at Frank Firk’s Essential Physics 1.

BONUS: Numerical Analysis (at least basic level) — A

lot of machine learning techniques out there are just fancy types of

function approximation. These often get developed by theoretical

mathematicians, and then get applied by people who don’t understand the

theory at all. The result is that many developers might have a hard time

finding the best technique for their problem. If they do find a

technique, they might have trouble fine-tuning it to get the best

results. Even a basic understanding of numerical analysis will give you a

huge edge. I would seriously look into Deturk’s Lectures on Numerical Analysis from UPenn, which covers the important topics and also provides code examples.

All

this math might seem intimidating at first if you’ve been away from it

for a while. Yes, machine learning is much more math-intensive than

something like front-end development. Just like with any skill, getting

better at Math is a matter of focused practice. There are plenty of

tools you can use to get a more intuitive understanding of these

concepts even if you’re out of school. In addition to Khan Academy, Brilliant.org is a great place to go for practicing concepts such as linear algebra, differential equations, and discrete mathematics.

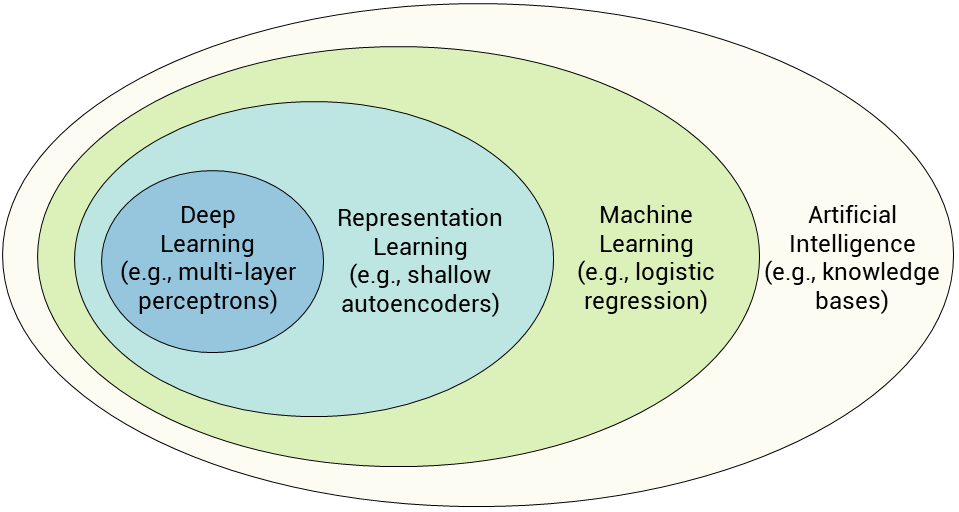

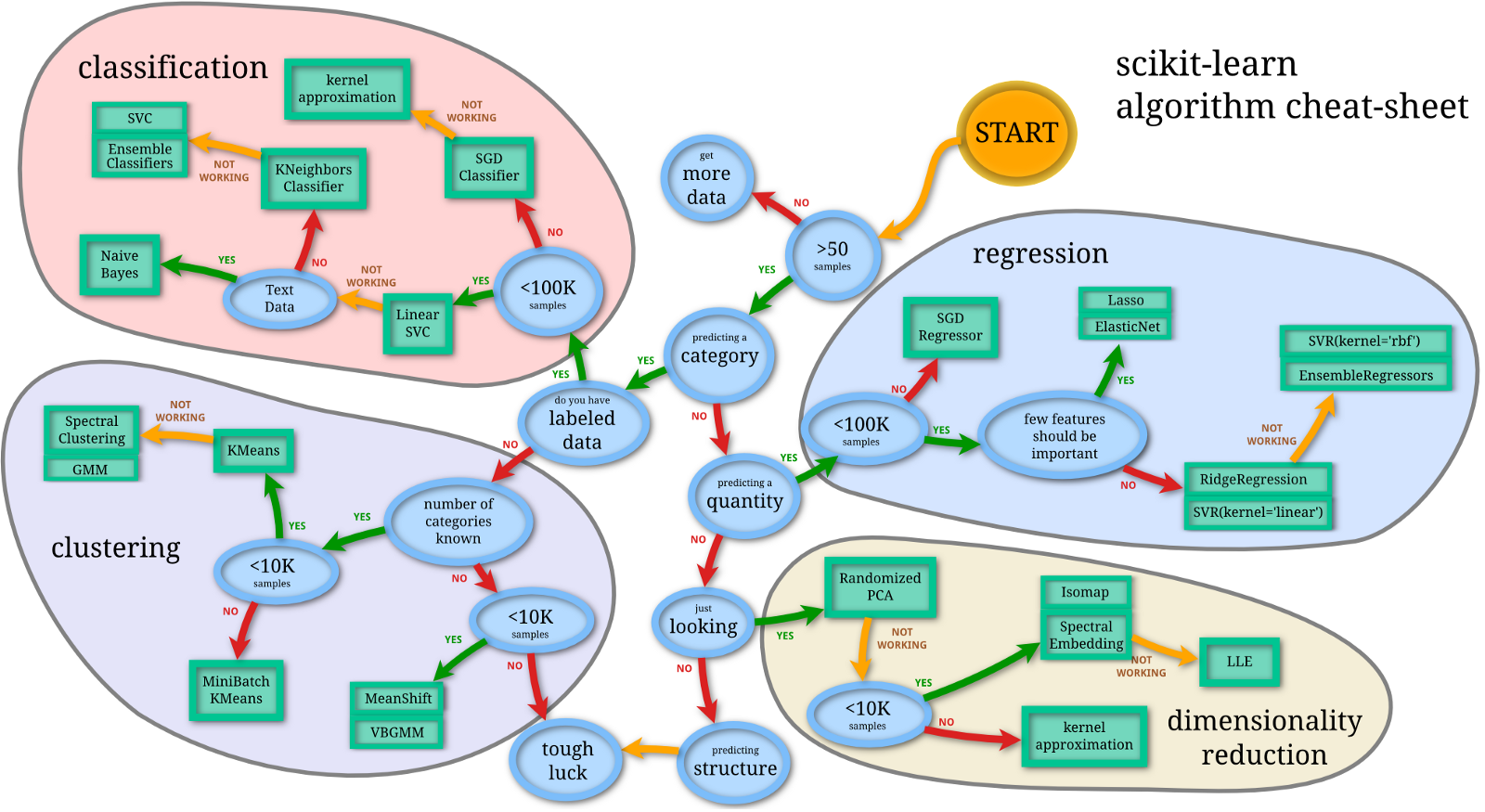

Common non-neural network Machine Learning Concepts — You

may have decided to go into machine learning because you saw a really

cool neural network demonstration, or wanted to build an artificial

general intelligence (AGI) someday. It’s important to know that there’s a

lot more to machine learning than neural networks. Many algorithms like

random forests, support vector machines (SVMs), and Naive Bayes Classifiers

can yield better performance for your hardware on some tasks. For

example, if you have an application where the priority is fast

classification of new test data, and you don’t have a lot of training

data at the start, an SVM might be the best approach for this. Even if

you are using a neural network for your main training, you might use a

clustering or dimensionality-reduction technique first to improve the

accuracy. Definitely check out Andrew Ng’s Machine Learning, as well as the Scikit-learn documentation.

Common Neural Network Architectures — Of

course, there are still good reasons for the surge in popularity of

neural networks. Neural networks have been by far the most accurate way

of approaching many problems, like translation, speech recognition, and

image classification. Andrew Ng’s Machine Learning (and his more up-to-date Deep Learning specialization) are great starting points. Udacity’s Deep Learning is also a great resource that’s more focused on Python implementations.

Bear

in mind, these are mainly the skills you would need to meet the minimum

requirements for any machine learning job. However, chances are you’ll

be working on a very specific problem within Machine Learning. If you

really want to add value, it will help to specialize in some way beyond

the minimum qualifications.

Specialized Skills and Subdisciplines

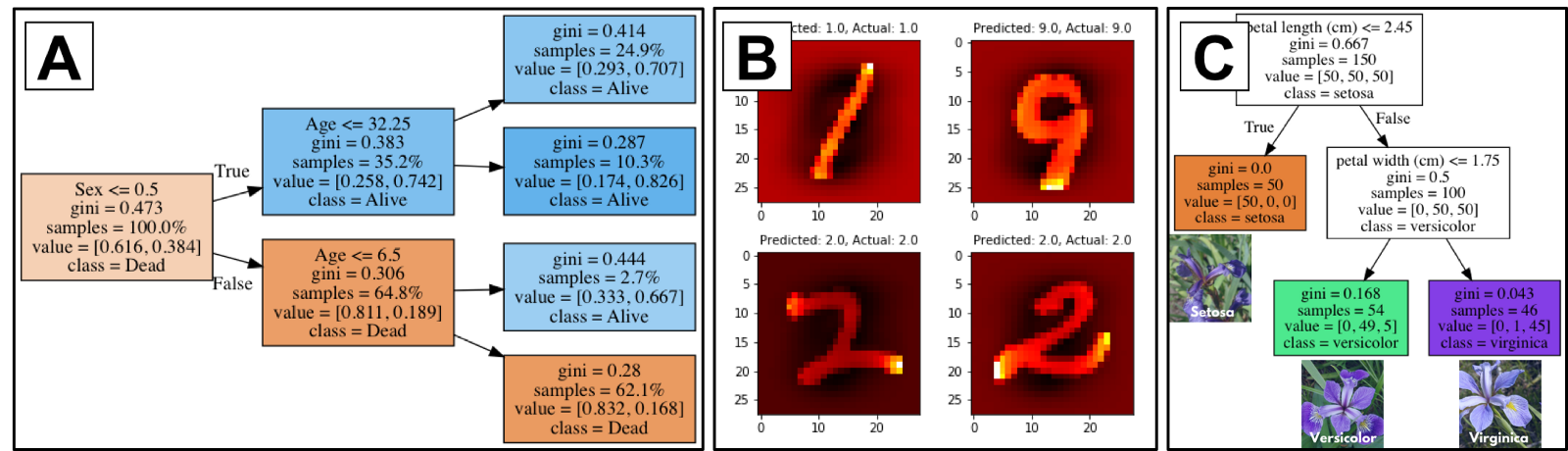

Computer Vision — Out of all the disciplines out there, there are by far the most resources available for learning computer vision. Getting a convolutional neural network to get high accuracy on MNIST

is the “hello world” of machine learning. This field appears to have

the lowest barriers to entry, but of course this likely means you’ll

face slightly more competition. A variant of Georgia Tech’s Introduction to Computer vision is available for free on Udacity. This is great if you supplement this course with O’Reilly Learning OpenCV and Richard Szeliski’s Computer Vision: Algorithms and Applications (he’s the founding director of the Computational Photography group at Facebook). I also recommend checking out the Kaggle kernels for Digit recognition, Dogs vs Cats classification, and Iceberg recognition.

Natural Language Processing (NLP) — Since it combines computer science and linguistics, there are a bunch of libraries (Gensim, NLTK) and techniques (word2vec, sentiment analysis, summarization) that are unique to NLP. The materials for Stanford’s CS224n: Natural Language Processing with Deep Learning class are readily available to non-Stanford students. I also recommend checking out the Kaggle kernels for the Quora Question Pairschallenge and Toxic Comment Classification Challenge.

Voice and Audio Processing — This

field has frequent overlap with natural language processing. However,

natural language processing can be applied to non-audio data like text.

Voice and Audio analysis involves extracting useful information from the

audio signals themselves. Being well versed in math will get you far in

this one (you should at least be be familiar with concepts like fast

Fourier transforms). Knowledge of music theory also helps. I recommend

checking out the Kaggle kernels for the MLSP 2013 Bird Classification Challenge and TensorFlow Speech Recognition Challenge, as well as Google’s NSynth project.

Reinforcement Learning — Reinforcement

learning has been a driver behind many of the most exciting

developments in deep learning and artificial intelligence in 2017, from AlphaGo Zero to OpenAI’s Dota 2 bot to Boston Dynamics’s Backflipping Atlas.

This is will be critical to understand if you want to go into robotics,

Self-driving cars, or any other AI-related area. Georgia Tech has a

great primer course on this available on Udacity. However, there are so many different applications, that I’ll need to write a more in-depth article later in this series.

There

are definitely more subdisciplines to ML than this. Some are larger and

some have yet to reach maturity. Generative Adversarial Networks are

one of these. While, there is definitely a lot of promise for their use in creative fields and drug discovery, they haven’t quite reached the same level of industry maturity as these other areas.

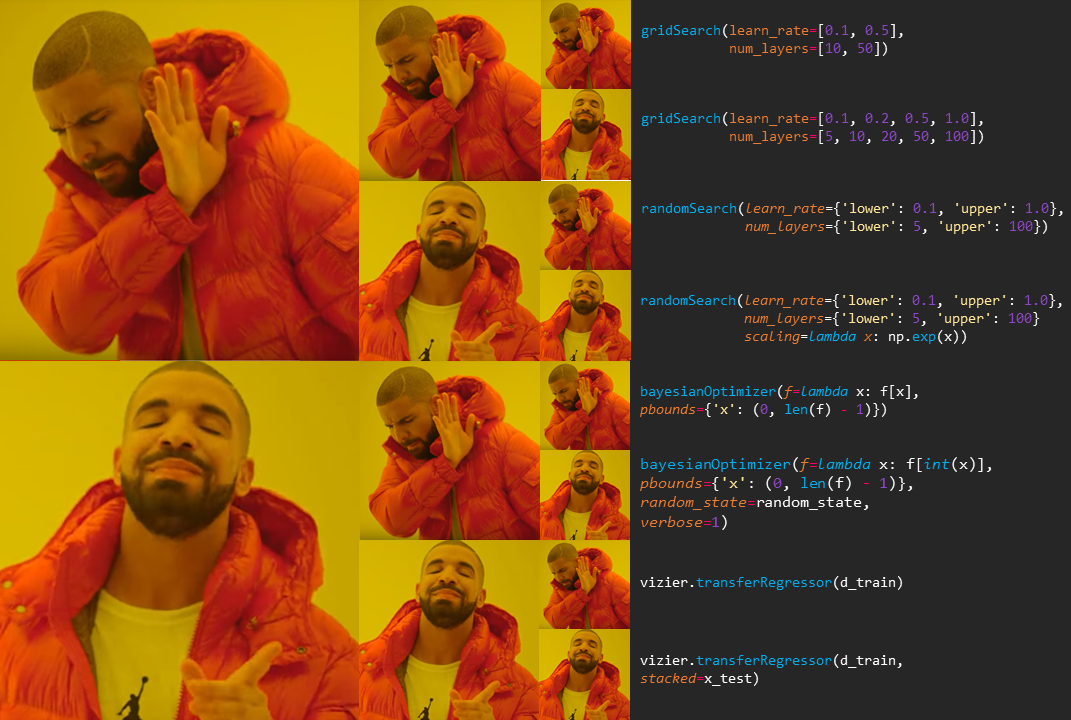

BONUS: Automatic Machine Learning (Auto-ML) — Tuning

networks with many different parameters can be a laborious process (in

fact, the phrase “graduate student descent” refers to getting hordes of

graduate students to tune a model over the course of months). Companies

like Nutonian (bought by DataRobot) and H2O.ai have recognized a massive need for this. At the very least, knowing how to use techniques like grid search (like scikit-learn’s GridSearchCV)and random search will be helpful no matter your subdiscipline. Bonus points if you can implement techniques like bayesian optimization or genetic algorithms.

Conclusions

With

this overview of machine learning skills, you should hopefully have a

better grasp on how the different parts of the field relate to one

another. If you want to get a quick, high-level understanding of any of

these technical skills, Siraj Raval’s YouTube channel and KDnuggets are good places to start.

It’s

not enough to just have this list of subjects in you head though.

Certain approaches to studying this are more effective than others.

Part 3: Immersion and Finding Mentors

Self

study can be tricky, even for those of us without any kind of attention

deficit disorder. It’s especially important to note that not all self

study is equal in quality. Take studying a language, for example. Many

people have had the experience of learning a language for years in a

classroom setting. When they go spend a few weeks or months in a country

where that language is all that is spoken, they often describe

themselves as learning much more quickly than in the classroom setting.

This is often referred to as learning a language by immersion. This means that even the instructions for what you need to do with a language are in the language itself.

While

learning a subject like machine learning might be functionally

different than learning another spoken language (you’re not going to be

speaking in classes and functions, after all), the principle of

surrounding yourself with a subject and filling as many hours of the day

with it is important here. That is what we’re talking about when we

talk about immersion with respect to machine learning. What Cal Newport

might say is that the reason formal institutions often consistently

result in higher quality is immersion for non-language subjects. People

spend many hours per day in structured settings where it’s almost

difficult NOT to study a particular subject. The ones that find more

immersion (i.e., taking additional more advanced classes, spending more

time studying the subject with others, involving themselves in original

research efforts) are the ones that succeed more.

If

you’re studying machine learning in a formal setting, good for you.

Much of the rest of the advice in this post still applies, but you’ve

got an edge. If you’re not studying machine learning in a formal

setting, or if you’re entering into the space from a different field,

your challenge is going to be building your own habits, commitments,

structures, and environments that make you spend as much time studying

machine learning.

How

do you do this? First, you’re going to need to put together a schedule

for learning the different subjects listed in the previous section. Fow

varied this is or how long it will take will depend on your previous

familiarity with the mathematical concepts involved (try starting with 1

week for reviewing each of the subjects to get a sense for the space,

and spend more or less time based on your previous familiarity).

You

should try to fit at least 2 hours into each day studying. EVERY.

SINGLE DAY. This spaced repetition will become stronger as your learning

streaks get longer (and you will be surprised at how rusty you can get

after taking just a single day off). If you can fit more than 2 hours

into certain days, like on weekends, that’s even better. Even when I was

working full time, I was making sure to fit at least 2 hours of

studying each day (part of this was the result of learning how to

effectively read papers, books, and tutorials while also riding a train

or bus). While there were occasionally holidays that I would use for

structured study-sessions, most of this found time came from

relentlessly optimizing what I spent my time doing.

You

should make sure to have a minimum amount of time each day scheduled in

your calendar (and I mean actually reserved in your calendar, in a slot

where nothing else can be scheduled over). Set up alerts for these

times, and find an accountability buddy (someone who can keep you

accountable if you do not study during these times. In my case I had

other friends that were studying subjects in machine learning and we

would present each other with our notes and/or github commits). 2 hours a

day minimum can sound like a lot, but if you remove the items from your

schedule that are less important (*cough* social media), you will be amazed at how much time you can find.

Now

at this point, much of the content has focused on what you as an

individual can to do improve your studying. There’s one more thing to

keep in mind when studying:

DON’T GO IT ALONE.

You’re

probably inexperienced in machine learning if you’re looking for advice

form this post. For the self study, it is absolutely critical that you

find a network of mentors (or at the very least one incredibly

experienced mentor). If you don’t find a mentor, you will have to put a

lot more time and effort into self-study to get the same results as

someone that had a mentor and put in less practice. Our culture is

flooded with the trope of the lone Genius. Many may correctly point out

that people like Mozart and Einstein became masters in their fields by

putting in thousands of man-hours while they were still young. However,

many of the same people often ignore the critical roles that mentors

played in their careers (Mozart had his father, and Einstein had

professors in one of the best physics departments on the planet at the

time).

Why

is finding a mentor so important? Chances are they may have been down

the same road you’re travelling. They have a better map of the space,

and will probably have a better grasp of the common pitfalls that plague

people earlier in their careers. They’ll be able to tell you whether

the machine learning idea you’re working on is truly novel, or whether

it’s been done countless times with a non-ML implementation

There are a few possible steps to acquiring a mentor

- Create a list of prospective mentors: Create a list of experienced people in the field of interest (in this case it might be computer science or machine learning). This list can be updated as time goes on, and you get a better feel for how everyone is connected in the space. You might be surprised at what a small world the machine learning space is.

- Be indirect at first: If you’re talking to a potential mentor for the first time, start out with very specific questions about their work. Demonstrate your interest by showing you’ve put thought into your questions (ask the kinds of questions where it seems like you’ve exhausted other research resources, and are coming to them because nobody else would have a good answer). Also, for those on your list, I would avoid asking literally “will you be my mentor?”. If the person in question is qualified to be a mentor, then they may not have a lot of time to spare in their schedule (especially not for something that sounds like it would require committing a lot of time to a person they just met). That leads me to the much better strategy…

- Demonstrate value: Again, if a person is experienced enough to be a good mentor, chances are they will also have very little spare time on their hands. However, they will often be willing to provide advice or mentorship if you’re willing to help them out with a project of theirs. Offer to volunteer. yes, I know unpaid internships can be considered dubious, but at this point in time getting a good mentor at all is more important. This can be a short term project that could turn into a referral for a much more rewarding one.

- Use youth to your advantage (if possible): If you are young, you might have an advantage. People are a lot more willing to help simply if you are younger. You might be nervous about approaching people a lot older, but you actually have a lot less to fear than you realize. The worst they can do is say no.

- Be open to reverse mentors: By reverse mentors, I mean people that are younger than you, but that are also much further ahead in their machine learning journeys. You may have come across people that have been programming since they were 5 years old, built their first computer not from a kit, but completely from scratch. They’ve started ML companies. They’re grad students at top CS programs. They’re Thiel fellows or Forbes 30 under 30s. If you happen to run into these people, do not be intimidated or envious. If you have someone like this in your network as a machine learning expert, try to learn from them. I’ve been fortunate enough to meet a bunch of people like this, and they were invaluable in helping me find the next steps.

- Be humble and obedient: It’s important that you remember you are coming to them for advice. They are taking time out of their busy schedule to give you recommendations. If you want someone to remain your mentor, then you should defer to their judgement. If you do something different than what they say or don’t do it at all, that will be a pretty good signal them that you either don’t value their advice, or that you aren’t that serious about becoming a machine learning engineer.

If

you focus on making sure you get as much immersion as possible, and you

are able to find experienced machine learning engineers to provide

advice and guidance, you’re off to a fantastic start.

There is one, last, minor detail to consider before you begin your learning journey…. you need an actual computer to program on.

Part 4: Software and Hardware Resources

Programming

for machine learning often distinguishes itself from web programming by

the fact that it can be much more demanding in terms of hardware. When I

started out on my machine learning journey, I originally used a

3-year-old Windows laptop. For basic machine learning tutorials this may

be adequate, but once you try spending 28 hours training a simple

low-resolution GAN, hearing your CPU scream in agony the whole time,

like me you will realize you need to expand your options.

The choice of environments can be daunting at first, but it can easily be split up into a parseable list.

The

first thing you may be wondering is whether you should pick Windows,

Mac, or Linux. A lot more packages, like you would see with Anaconda,

are compatible with Mac and Linux rather than Windows. Tensorflow and

PyTorch are available on all 3, but some less common but still useful

packages like XGBoost may be trickier to install on Windows. Windows has

becoming more popular in recent years as a development platform for

machine learning, though this has largely been due to the emergence of

more cloud resources with Azure. You can still use a Windows machine to

run software that was developed for Mac or Linux, such as by setting up a

VirtualBox virtual machine. It’s also possible you could use a Kaggle

kernel or a databricks kernel, but that of course is dependent on having

a great internet connection. For the operating system, if you’re

already used to using a Mac you should be fine. Regardless of which

operating system you choose, you should still try to add an

understanding of Linux to your skill set (in part because you will

probably want to deploy trained models to servers or larger systems of

some kind.

For

your machine learning set up, you have four main options: 1) the Laptop

Option, 2) Cloud Resources/Options, 3) Desktop Option and 4) Custom/DIY

Machine Learning Rigs.

Laptop Option: Favoring portability & Flexibility — If

you’re going for the machine learning freelancing route, this can be an

attractive option. It can be your best friend if you’re a digital nomad

(albeit, one that might feel like a panini press if you’re keeping it

in your actual lap when you’re using it for model training). With that

in mind, here are some features and system settings you should make sure

you have if you’re using your Laptop for Machine Learning.

- RAM: Don’t settle for anything less than 16 GB of RAM.

- GPU: This is probably the most important feature. Having the right GPU (or having any GPU instead of just CPUs) could mean the difference between model training taking an hour or taking weeks or months (and making lots of heat and noise in the process). Since many ML libraries make use of Cuda, go with an NVIDIA graphics card (like a GeForce)for the least amount of trouble. You may need to write some low-level code for getting your projects to run on an AMD card.

- Processor: Go with an Intel i7 (if you’re a Mr. Krabs-esque penny-pincher, make sure you don’t go below an Intel i5).

- Storage: Chances are you’re going to be working on projects that require a lot of data. Even if you have extra storage on something like Dropbox or an external drive, make sure you have at least 1 TB.

- Operating System: Sorry Mac and Windows cultists, but Skynet is probably going to be running on Linux when it comes out. If you don’t have a computer with Linux as the main OS yet, you can make a temporary substitute by setting up a virtual machine with Ubuntu on either your Mac or Windows machine.

When it comes to specific brands there are many choices. Everyone from Acer to NVIDIA has Laptops.

My personal choice? I went with a laptop specialized for machine learning from Lambda Labs.

Of

course, if you insist on using a Mac, you could always connect your

machine to an external GPU (using a device like an NVIDIA Pascal)

But if you’re strapped for cash, don’t fear. You can always go with one of the cheapest laptops out there (e.g., a $249 Chromebook),

and then use all the money you saved for cloud computing time. You

won’t be able to do much on your local machine, but as long as you have a

decent internet connection you should be able to do plenty with cloud

computing.

Speaking of cloud computing…

Cloud Resources/Options — It’s

possible that even your powerful out-of-the-box or custom build won’t

be enough for a really big project. You’ve probably seen papers or press

releases on massive AI projects that use 32 GPUs over many days or weeks.

While most of your projects won’t be quite that demanding, it will be

nice to have at least some options for expanding your computing

resources. These also have the benefit of being combined with whatever

laptop you have, combining it

Microsoft

Azure is usually the cheapest for compute time (I might be fanning the

flames of the Github/Gitlab holy war here). Amazon usually has a lot

more options (including more obscure options like combining it with data

streaming Kinesis or long term storage in S3 or Glacier). If you’re

using a Tensorflow Model, Google Cloud’s TPUs (i.e., re-marketed GPUs)

are optimized for models built using this. They also offer tools and

services for optimizing your hyperparameters, so you don’t have to set

up the bayesian Optimization yourself.

If

you’re relatively new to using Cloud Services, Floydhub is the simplest

to use in terms of user experience. If you’re a beginner, this is by

far the easiest one to set up.

Then

again, you might not find the idea of shelling out a bunch of money for

GPU compute-time for every project you want to do. At some point, you

may decide to yourself that you only want to concern yourself with the

electric bill when it comes to compute power, nothing else.

Desktop Option: Powerful and reliable — If

you don’t want to have variable costs due to cloud computing bills, and

you don’t want your important machine learning work to be at risk for

environmental damage, another option could be to set up a Desktop

environment. Lambda Labs and Puget Systems

make some really great high-end desktops as well. The hardware options

for a desktop can take a bit more skill to navigate, but here are some

general principles to keep in mind:

For

the GPU, go with an RTX 2070 or RTX 2080 Ti. If cost is a concern,

going with a cheaper GTX 1070, GTX 1080, GTX 1070 Ti, or GTX 1080 Ti can

also be a good option. However many GPUs you have, make sure you have

1–2 GPU cores per GPU (more of you’re doing a lot of preprocessing). As

long as you buy at least as much CPU RAM to match the RAM of your

largest GPU, go with the cheapest RAM that you can (Tim Dettmers has a post explaining how the clock rates make little meaningful difference). Make sure the hard drive is at least 3 TB in size.

If

possible, go with a solid-state drive to improve the speed for

preprocessing small datasets. Make sure your setup has adequate cooling

(this is a bigger concern for Desktops than for laptops). As for

monitors, I’d recommend putting together a dual-monitor setup (3 may be

excessive, but knock yourself out. I don’t know what you would use 4 for

though).

Downside?

Basic models will cost about $2,000 to $3,000, with high-end machines

costing around $8,897 to $23,000. This is much steeper than the laptop

option, and unless you’re training complex models on massive datasets,

this is probably outside your initial budget for cloud computing.

However,

there is a big advantage that desktops have over laptops: Since desktop

computers are less restricted by design constraints such as

portability, or not turning your lap into a panini press from the heat radiating from it, it is far easier to build and customize your own. This can also be a fantastic way to cheaply build your ideal machine.

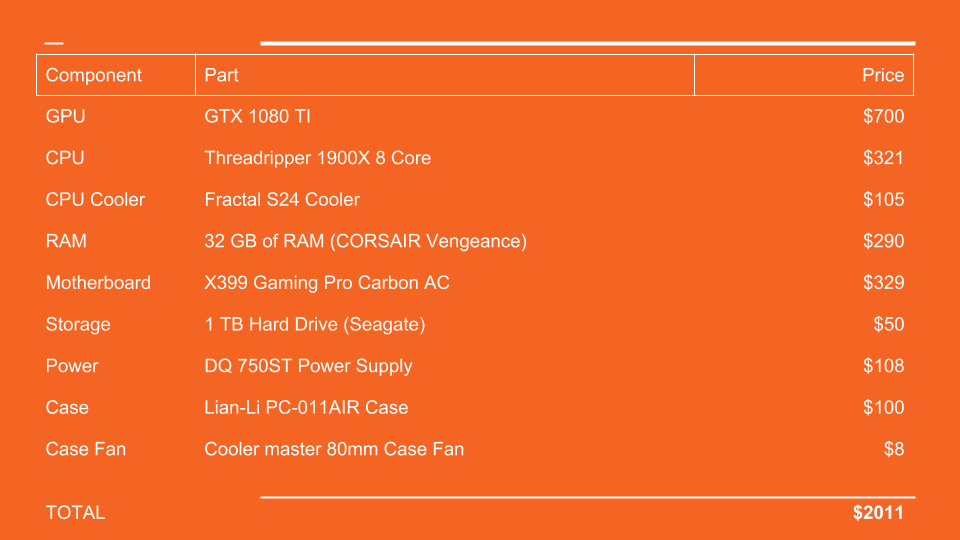

Custom/DIY Machine Learning Rigs: For the enthusiast — Chances

are if you’re in the field for a while, you’re going to start wanting

to build your own custom computer. It’s an inevitable consequence of

thinking about how much GPU resources you’re spending on a project for

this long. Given that the development of the GPUs that made cheap and

effective machine learning was pretty much subsidized by the gaming

industry, there are plenty of resources out there on building your own

PC. Here is an example breakdown of a few components and their prices.

These were intentionally selected for being cheap, so you could easily

replace any of the parts with something higher-end.

It’s

entirely possible that your level of comfort with hardware might not be

on the same level as your software comfort. If that’s the case,

building your PC is certainly going to be a lot (and I mean A LOT)

trickier than it is in PC Building Simulator. If you do succeed, this

can be a fun project, and you’ll also save money on a desktop machine

learning rig

With the custom build, you also have the option for some pretty out-there options as well…

Whichever

setup you choose, whether it be mainly Laptop, Cloud-based, Desktop, or

custom build, you should now be more than ready to run your own machine

learning projects.

Of

course, becoming a machine engineer is about more than just setting up

your hardware/software environment correctly. Since the field is

changing so much, you’re going to need to learn how to read research

papers on the subject.

Part 5: Reading Research Papers (and a few that everyone should know)

In

order to have a proper understanding of machine learning, you need to

get acquainted with the current research in the space. It’s not enough

to agree with claims of what AI can do, just because it got enough hype on social media.

If you have GPU resources, you need to know how to properly utilize

them or else they’ll be useless. You need to learn to be critical and

balanced in your assessment. This is what PhD students learn how to do,

but luckily you can also learn how to do this.

For finding new papers to read, you can often find them by following machine learning engineers and researchers on Twitter. The machine learning subreddit

is also another fantastic resource. Countless papers are available for

free on Arxiv (and if navigating that is too intimidating, Andrej

Karpathy put together archive sanity to make I easier to navigate). Journals like Nature and Science can also be good sources, too (though Arxiv often has much more, and without paywalls).

Usually there about 2 or 3 papers that are particularly popular in any given week.

For

getting through a paper, it usually helps if you have some kind of

motivation for getting through it. For example, if I want to learn about

influence functions or Neural ODEs,

I will search through the papers and read them until I understand them.

As was mentioned before with the immersion, how far you get is going to

be a function of discipline, which in turn is going to be influenced

even further by your motivation.

For any given paper, there are certain techniques you can use to make the information easier to digest and understand. The book “How to read a book”

is a fantastic resource that described this in detail. In short, you

can use what is known as a three-pass approach. In the first pass

through the paper, you can just skim through the paper to see if it is

interesting. This means you first read the title, and if it’s appealing

move onto the abstract. The abstract is the short summary at the

beginning that covers the main points in the papers. If that seems good,

you move onto the introduction, read through that, then read the

section and subsection headers, but not the content of those sections.

In the first pass, you can temporarily ignore the math (assume it’s

sound for now). Once you go through the section headers, you read the

conclusion, and then skim through the references. In the references, if

you see any papers that you’ve read before, you can mark those. The

whole purpose of this first pass is to understand what the purpose of

the paper is, what the authors are trying to do, what problem they are

trying to solve. After the first pass, I will usually turn to Twitter

(or whatever source the paper came from), and compare what others are

saying about the paper to my initial assumptions.

If

after all this I have determined that the paper is interesting enough

to read more in-depth, I’ll take another pass through it. I’ll try to

get a high level understanding of the math in the paper. I’ll read the

thicker descriptions, the plots, and try to understand the high-level

algorithm. I’ll usually pay more attention to the math this time around.

However, there may be times where the author tries to factor out all

the math. On the second pass I’m still not going through these

factorizations and derivations just yet. When I read the experiments, I

will try to evaluate whether the experiments seem reproducible. If there

is code available on Github for this paper, I will usually follow the

Github link and read through the code, and perhaps even try running some

part of it on my own device. Usually comments in the code help with

understanding. I will also read through other online resources online

that help with understanding (the more popular papers often have plenty

of high-level summaries, such as on sites like ML Explained).

On

the 3rd pass, this is when you try to understand the math itself. At

this point, you will be going through the paper with a pen and notepad,

and following along with the math itself. If there are any mathematical

terms or concepts that you do not understand, this is the point where

you search online for better explanations. If you’re really ambitious,

you can also try replicating the paper in code form, complete with the

parameters and data that they use in the paper.

If

at any point you feel stuck or frustrated, just remember to not give

up. persistence will get you very far, and reading papers gets much

easier the more times you do it. If you’re still stuck on the math,

don’t hesitate to turn to Khan Academy or Wikipedia. If you’re looking

for even more help, try reaching out on the Machine Learning Subreddit,

or join a journal club meetup group in your city.

As

for which papers to start with, I would try applying the technique

above to some of the classic papers in machine learning. A lot of the

papers you read (especially the avalanche of GAN papers out there) will

have many concepts from these. I’ve listed a few of the big ones by

subject and included links to the papers.

- For Computer Vision, AlexNet (2012), ZF Net (2013), VGG Net (2014), GoogLeNet (2015), and Microsoft ResNet (2015) are the big ones

- For image segmentation, Region Based CNNs (R-CNN — 2013, Fast R-CNN — 2015, Faster R-CNN — 2015) and YOLO

- Generative Adversarial Networks (2014)

- Generating Image Descriptions (2014)

- Spatial Transformer Networks (2015)

These

papers are a great starting point for a conceptual understanding of

where these large, daunting, machine learning models come from. While

this will take you very far in building projects and following the

latest developments, it also helps to know who is creating these developments.

Part 6: Groups and People you should be Familiar with

As

I mentioned before, finding mentors and reading papers are important.

However, it’s also worth paying attention to the work of specific

researchers.

Depending

on which subfield you go into, following certain individuals might be

more important than others, but generally speaking being familiar with

these ones will reduce the risk of you getting into an awkward moment at

NIPS. Since many of these groups are also the most heavily-connected,

you can probably navigate the increasingly crowded machine learning

research space by traversing a mental graph of who is connected to who,

and through whom.

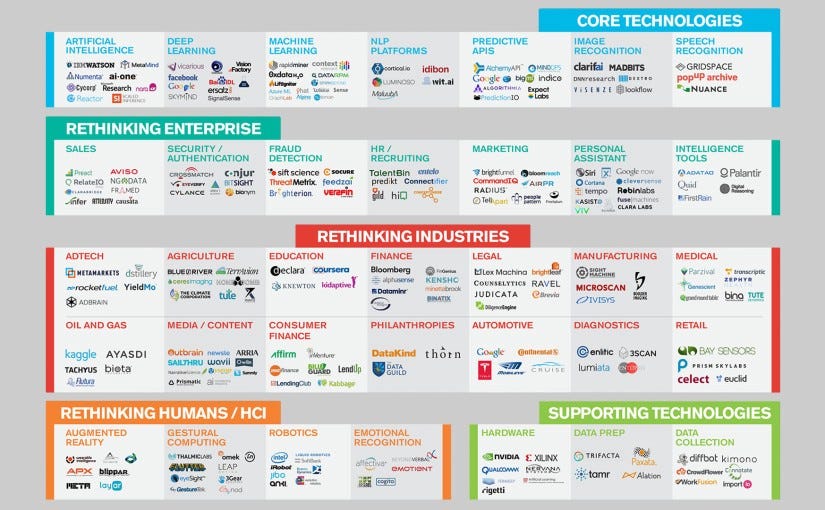

For companies, there are the big ones you should be aware of: Deepmind (Google), Google Brain, Facebook (AI Lab), Microsoft Research (AI Lab), OpenAI.

These are the ones that get the most press, but it’s also worth keeping

in mind some of the smaller groups. These include but are not limited

to Vicarious, Numenta, MIRI, Allen Institute, IBM (Watson), Vision Factory (acquired by Google DeepMind), Dark Blue Labs (also acquired by Google DeepMind), DNNresearch (not acquired by Google DeepMind, but acquired by Google Brain), NNAiSene, Twitter Cortex, Baidu (AI Lab), Amazon (AI Lab), and Wolfram Alpha.

These

companies often get a lot attention for research in the ML space

because they often have much more computing resources (and can pay the

researchers more) than in academia. However, that’s not to say there

aren’t plenty of Academic research centers you should be aware of. These

include (but again, are not limited to) IDSIA (Dalle Molle Institute for Artificial Intelligence Research, Juergen Schmidhuber’s Lab), MILA — Montreal Institute of Learning Algorithms, University of Toronto (as a whole, since so many researchers like Ian GoodFellow and Geoffrey Hinton have come out of there), and Gatsby.

For researchers, Demis Hassabis (Co-founder of DeepMind), Shane Legg (Co-founder of DeepMind), Mustafa Suleyman (head of product at DeepMind), Jeff Dean (Google), Greg Corrado (Google AI Research Scientist), Andrew Ng (Stanford, Coursera), Ray Kurzweil (Transhumanism, computer vision, and too much else to list here), Dileep George (Vicarious), D. Scott Phoenix (Vicarious and Numenta), Yann Lecun (creator of CNNs, you should probably make sure you know this guy), Jeff Hawkins (Numenta, Palm Computing, and Handspring), and Richard Socher

(Salesforce, Stanford) are good ones to keep in mind. Like the list of

companies, this should not be considered a comprehensive list. Rather,

since many of these people are superconnectors within the machine

learning space, you can gradually build up a graph to connect the most

prominent people. If you want to stay connected and aware without

information overwhelm, twitter is a fantastic tool (just keep the number

of people you’re following to under 1,500 and triage accordingly), as

well as newsletters like Papers with Code, O’Reilly Data Newsletter, KDNuggets News, and the Artificial Intelligence Podcast by Lex Fridman.

Of

course, it’s not enough to be familiar with the current celebrities of

machine learning. You should probably also make yourself familiar with

historical figures such as Charles Babbage, Ada Lovelace, Alan Turing. I

recommend Walter Isaacson’s “The Innovators” for an overview of the connection for all of them.

Again,

I should stress that your map of the organizations and prominent

researchers here should not be limited by this list. As with anything in

machine learning, you are going to need to continually update your

knowledge-base, and figure things out for yourself.

Speaking of figuring things out for yourself…

Part 7: Problem-Solving Approaches and Workflows

The

ultimate goal behind reading many research papers, working on many

projects, and understanding the works of top researchers is to better

develop your own approaches. While the workflows of top researchers can

be attributed at least partially to intuition from having seen so much,

there are still some general patterns and steps you can take for

undertaking a machine learning project. Many of these apply for

everything from original research to developing models for freelance

clients.

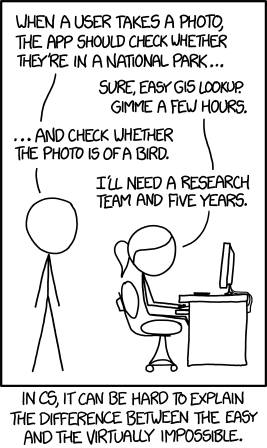

Determine if Machine learning is actually necessary:

It’s of course not as simple as throwing a neural network at

everything. First off, you might want to make sure that for the problem

you’re working on Machine learning will actually be an improvement over

some other algorithm. You wouldn’t use a neural network to solve FizzBuzz, riiiiiiiight?

Understanding the type of problem: Once

you’ve determined that using machine learning would be beneficial, you

probably want to determine what specific type of machine learning is

useful (or even if a pipeline with multiple steps would be useful). Are

you trying to get a model that matches patterns in known data? You’re

probably using Supervised learning. Are you trying to uncover patterns

you’re not sure exist? It’s likely unsupervised learning that you’re

working on. Are you working with data that changes after each output

from your model? You’re probably going down the reinforcement learning

path.

Check Previous work: It

is a wise precaution to see what other previous work has been done on a

problem. Take a scan of Github to get some ideas. It’s also worth

looking into existing literature on a specific problem.

Image-processing, for example, has so many solutions that some refer to

it as a solved problem. Facebook’s AIs can already recognize human faces

with much greater accuracy than most humans. That being said, it’s

likely you will get to a point where even the best existing solutions

are inadequate (i.e., pretty much the state of the entire field of NLP

for many tasks). When it comes to that, there are a variety of different

steps you can incorporate into solving a problem.

Preprocessing and Exploratory Data Analysis: Before

you input the data into your model, you should always stop to make sure

your dataset is up to snuff. This can involve everything from checking

for missing data, to rescaling and filtering the data, to looking at the

relationships between parts of the data at a basic level.

For

preprocessing, one common technique is to use a zero mean (subtract the

mean from each predictor) to center the data, which can be combined

with dividing by standard deviation to scale the data. This can be used

for anything from tabular data to RGB values in images. Dates and times

should be put into a consistent DateTime format. If you have a lot of

categorical variables, it is more often than not crucially important to

One-Hot encode them. At this stage you should also strive to resolve any

outliers (and if possible understand their meaning). If your model is

sensitive to outliers, you can try applying a spatial sign. You should

also make the effort to eliminate any missing data. This can obviously

be problematic if missingness is somehow predictive. Tree-based models

are great for deal with missing data, or if you don’t have time for that

you can use imputation/interpolation (KNN or intermediate regression

model).

The

exploratory data analysis can also be useful for getting an intuitive

sense for what kinds of models or data reduction techniques could be

useful. This is important for finding possible relationships between any

and all of the features you might be working with. Calculations such as

Maximal Information Coefficients can be useful. Building correlation

matrices for the features (i.e., box-charting everything),

scatter-plotting and histogram-plotting every combination of features

can expand this even more. Don’t get so excited about jumping into using

a k-NN classifier that you forget the techniques from simple excel

tables, such as using pivot tables and grouping by particular features.

Some of your variables might need to be transformed (square, cube,

inverse, log, Optimus…wait…what?)

before they can be plotted or models can be trained on them. For

example, if you’re looking at river flow events or cryptocurrency

prices, it will probably be wise to plot values on a log scale. While

you’re putting together the boilerplate for automatically doing all

these steps for whatever dataset you find, don’t forget the classic

summary statistics (mean, mode, minimum, maximum, upper/lower quartiles,

identification of >2.5 SD outliers).

Data Reduction:

When beginning a project, it’s a good first step to see if reducing the

amount of data to be processed will help with the training. There are

many techniques for this. You’ve probably heard of using Principal

Component Analysis (PCA) or Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA, in the

case of classification). Feature Selection, or only using the components

that account for a majority of the information when Modeling, can be

another easy way to focus on the important information to the model. How

do you decide what to remove? Removing low/zero variance predictors

(ones that don’t vary with the correct classification), or removing

multicollinear heavily correlated features (if there’s a 99% correlation

between two features, one of them is possibly useless) can be good

heuristics. Other techniques like Isomap or Lasso (in the case of

regression) can help even more.

Parameter tuning: Once

you do have your model running, i may not be performing exactly as you

wanted. Fortunately this can be solved with clever parameter tuning.

Unfortunately there are often many parameters for models like neural

networks, so some techniques like grid search may take longer than

anticipated. Unintuitively, using random search can give improvements

over grid search, but even then the dimensionality problem can remain.

There is a field focused on efficiently tuning large models. This can

involve anything from bayesian optimization, to training SVMs on data of

model parameters, to genetic algorithms for architecture search. That

being said, it is often the case that once you learn enough about the

techniques you’re using in a model (such as an Adam or AdaDelta

optimizer), you’ll begin to have an intuition for how to quickly

converge on ideal parameters based on the output of the training graphs.

Higher-level modelling techniques: We

covered the importance of feature engineering. This can cover

everything from basis expansions, to combining features, to properly

scaling features based on average values, median values, variances,

sums, differences, maximums or minimums, and counts. Algorithms such as

Random forest, boosters, and other tree-based models for finding the

important features. Clustering, or any models based on distances to

class centroids, can also be useful for problems where a lot of feature

engineering is needed.

Another

advanced technique is the use of stacking or blending. Stacking and

Blending are two similar approaches of combining classifiers

(ensembling). I recommend reading the Kaggle Ensembling Guide for more detailed information.

However

sophisticated your modelling techniques get, don’t forget the

importance of acquiring domain knowledge for feature engineering. This is a common strategy among Kaggle competition winners:

thoroughly researching the subject of the competition to better

influence their decisions for how to build their model. Even if you do

not have a lot of domain knowledge, you should be able to account for

missing data (It can be information), or add on additional external data

(such as with APIs).

Reproducibility: This

one is more a quality of workflows than problem-solving strategies.

You’re probably not going to do an entire project in one sitting. It’s

important to be able to pick up where you left off, or easily be able to

start from the beginning with only a few clicks. For model training,

make sure you set up your code to have the proper checkpointing and

weight-saving. Reproducibility is one of the big reasons why Jupyter

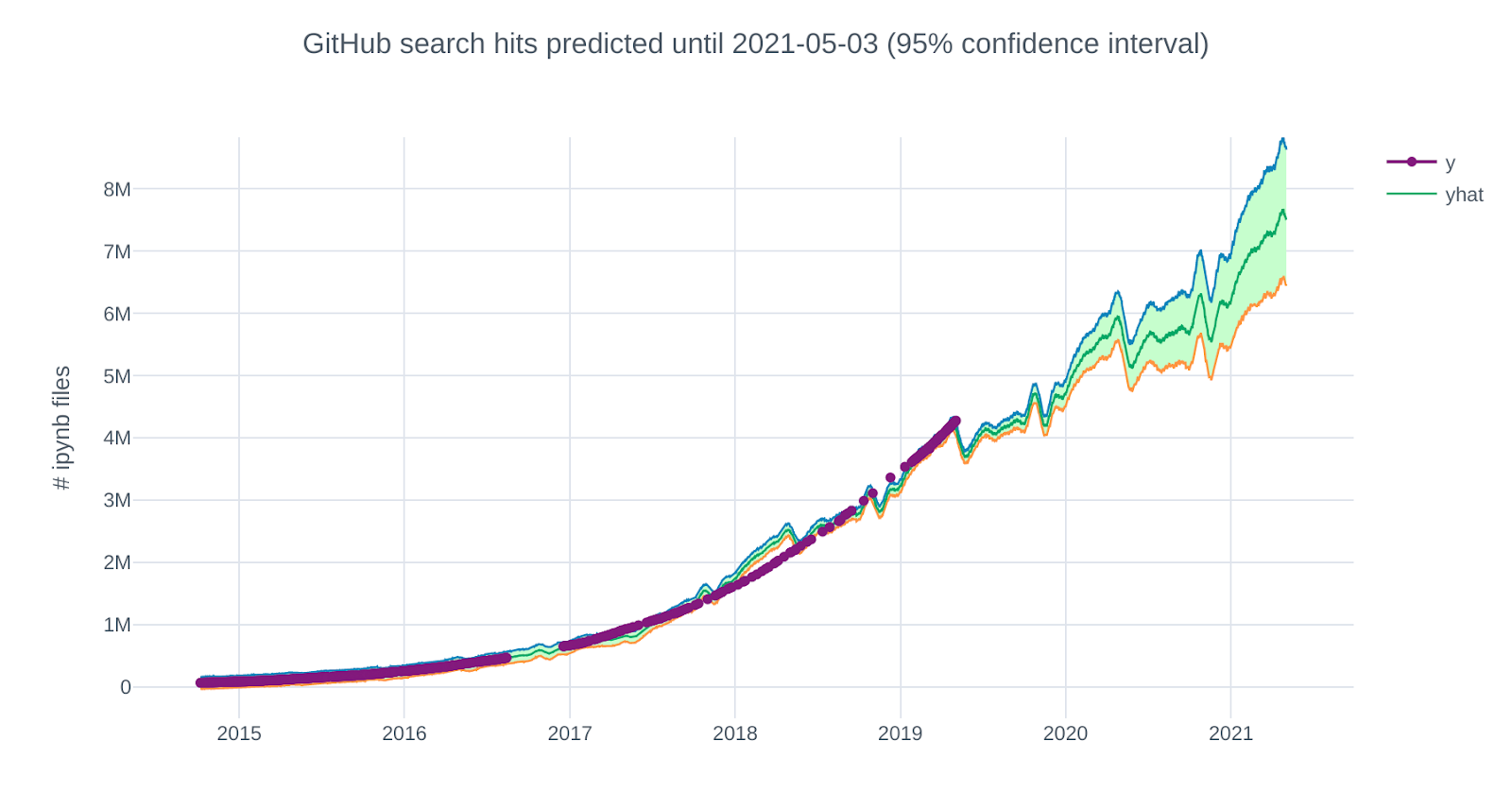

notebooks have gotten so popular in machine learning.

That

was a bit of a mouthful. I encourage you to follow the links within

there to learn more about the subjects. Once you have gotten the grasp

of these different strategies and workflows, the inevitable question is

what you should apply them to. If you’re reading this, your goal might

be to enter into machine learning as a career. Whether you do this as a

freelancer or a full-time engineer, you’re going to need some kind of

track record of projects. That’s where the portfolio comes in.

Part 8: Building your portfolio

When

you’re transitioning into a new career as a machine learning engineer

(or any kind of software-tangential career, not just ML), you may be

faced with an all too common conundrum: you’re trying to get work to get

experience, but you need experience before you can get the work to get

experience. How does one solve this Catch-22? Simple: Portfolio projects.

You

often hear about portfolios being a thing that front-end developers or

designers put together. It turns out this can be a crucial

career-booster for Data Scientists

and Machine Learning Engineers. Even if you’re not in the position of

looking for work just yet, the goal of building a portfolio can be

incredibly useful on its own for learning machine learning

What NOT to include in your portfolio

Before

we get into examples, it’s important to make it clear what should not

be included in your ML portfolio. For the most part, you have a lot of

flexibility when it comes to your portfolio. However, when it comes to

projects that could result in your resume being thrown in the trash,

there are 3 big ones that come to mind: Survival classification on the Titanic dataset. Handwritten digit classification on the MNIST dataset. Flower species classification using the iris dataset.

These

datasets are used so heavily in introductory machine learning and data

science courses, that having project based on these will probably hurt

you more than help you. These are the types of projects that are already

used in the example folders in many machine learning libraries, so

there’s probably not that many original uses for them.

Machine learning portfolio ideas

Now

that we have that warning out of the way, here’s some suggestions of

projects you CAN add to your machine learning portfolio.

Kaggle Competitions

Beyond Kaggle, there are other similar competitions out there. Halite

is an AI programming competition created by Two-Sigma investing. This

is somewhat more niche than Kaggle competitions, but it can be great if

you want to test your skills in reinforcement learning problems. The

only downside is that the competition is seasonal, and doesn’t have as

many frequent competitions as Kaggle, but if you can get your bot high

into the leaderboards when the next competition comes around, this can

be a great addition to your portfolio.

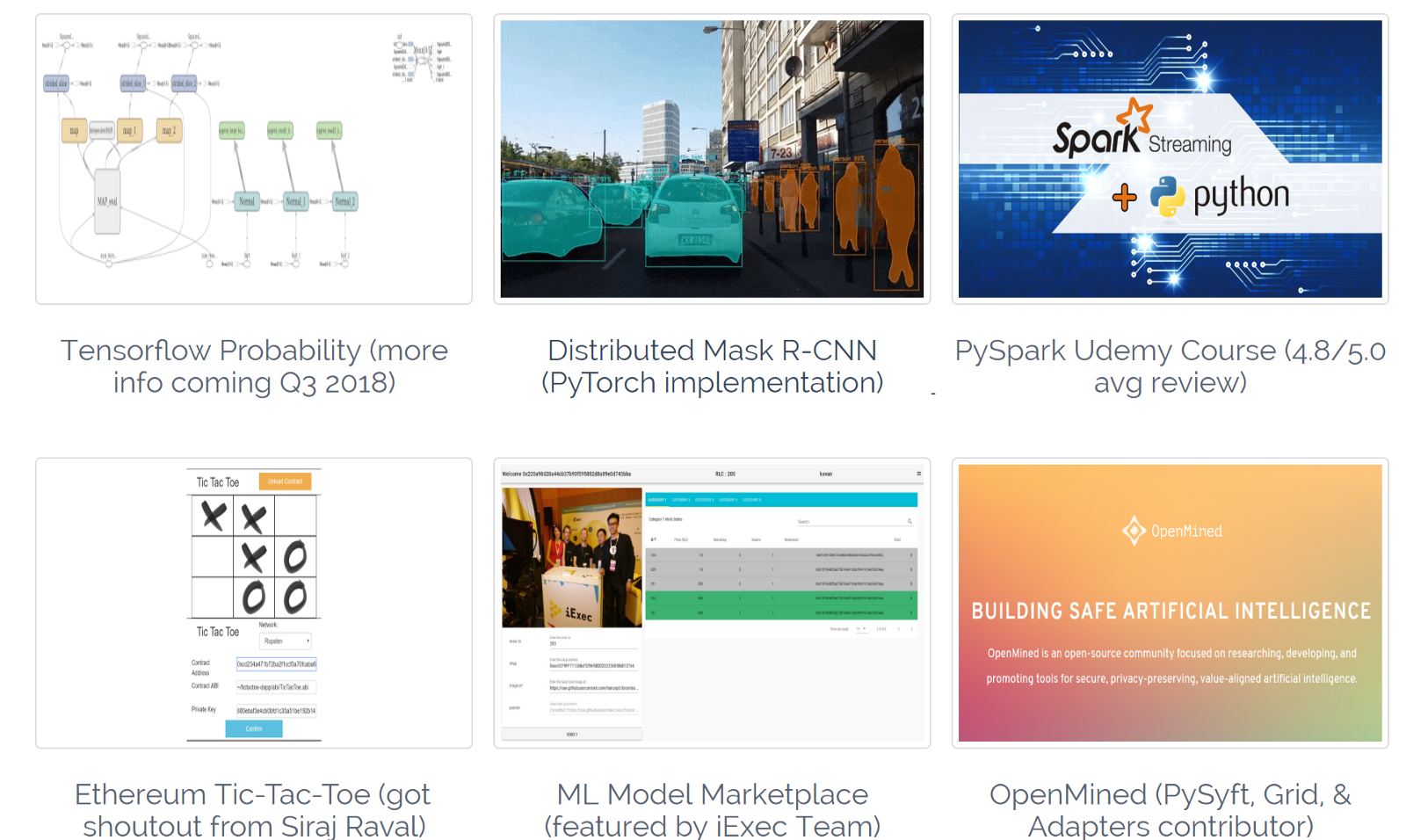

Implementations of Algorithms in Papers

Many

of the newer machine learning algorithms out there are first reported

in the form of scientific papers. Reproducing a paper, or reimplementing

a paper in a novel setting or on an interesting dataset is a fantastic

way to demonstrate your command of the material. Being able to code the

usual ML algorithms is one thing, but being able to take a description

of an algorithm and then turn it into a working project is a skill

that’s far too low in supply. This could involve reimplementing the

project in a different language (e.g., Python to C++), a different

framework (e.g., if the code for the paper was written in tensorflow,

try reimplementing in PyTorch or MXNet), or on different datasets (e.g.,

bigger datasets or less publically available datasets).

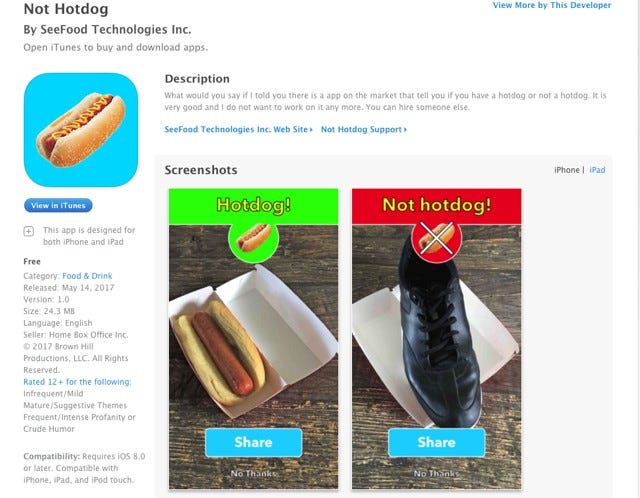

Mobile Apps with Machine Learning (e.g., Not Hotdog Spinoffs)

If

you’re looking for work in machine learning, chances are you won’t just

be making standalone JuPyter notebooks. If you can demonstrate that you

can integrate . Since libraries like tensorflow.js have come out for

doing machine learning in javascript, this is also a fantastic

opportunity to try integrating ML into react or react native

applications. If you’re really scraping the bottom of the barrel for

ideas, there’s always the classic “Not Hotdog” from HBO’s Silicon

Valley.

Of

course, copying the exact app probably won’t be enough (after all, the

joke was how poorly the app was prepared to handle anything other than hotdog and not hotdog.

What additional features can you add? Can you increase the accuracy?

Can you make it classify condiments as well? How big of a variety of

foods can you get it to classify? Can you also get it to provide

nutritional or allergy information?

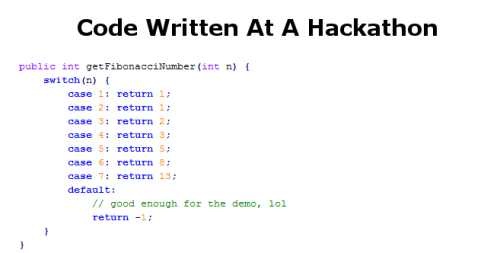

Hackathons and other competitions

In

the absence of anything else, projects are often judged based on the

impact they’ve had or the notoriety they’ve received. One of the easiest

ways to get an impressive project in this regard is to put a hackathon

project into your portfolio. I’ve taken this approach in the past with

projects I’ve done as part of hackathons at MassChallenge or the MIT

Policy Hackathon. Being a track or prize-winner can be a fantastic

addition to your portfolio. The only downside is that hackathon projects

(including the edge cases) are basically glorified demos. They are

often terrible at standing up to much scrutiny or edge cases. You may

want to polish you code a bit before adding it to your portfolio.

Don’t

feel the need to restrict yourself to these ideas too much. You can

also add any talks you’ve given, livestream demos you’ve recorded, or

even online classes you’ve taught. If you’re looking for any other

inspiration, you can take a look at my portfolio site as an example.

Above

all else, it’s important to remember that a portfolio is always a work

in process. It’s never something that you will 100%. If you wait until

that point before you start applying to jobs and advertising your

skills, you’ve waited too long.

Part 9: Freelancing as an ML developer

There

may be many areas of Machine Learning you might be interested in doing

research in. When it comes to getting hands-on experience and immersion.

Working on paid ML work is the next level up. It’s also incredibly easy

to get started.

For

sites to do freelancing on, I recommend turning to Upwork or

Freelancer. Freelancer requires payment for taking the skill tests on

their site, so Upwork may be superior in that sense (at least, that’s

why I chose it).

If

you’re looking to delegate more on the side of project management and

screening potential clients, Toptal might be a good option. Toptal

Screens potential clients for you, as well as provides support on

project management. The only downside is that they also heavily screen

freelancers as well (They advertise that they only hire the “Top 3% of

freelancers”. Whether or not that exact statistic is true, they are

nonetheless very selective). Becoming a freelancer with Toptal will

require passing a timed coding test, as well as passing a few

interviews.

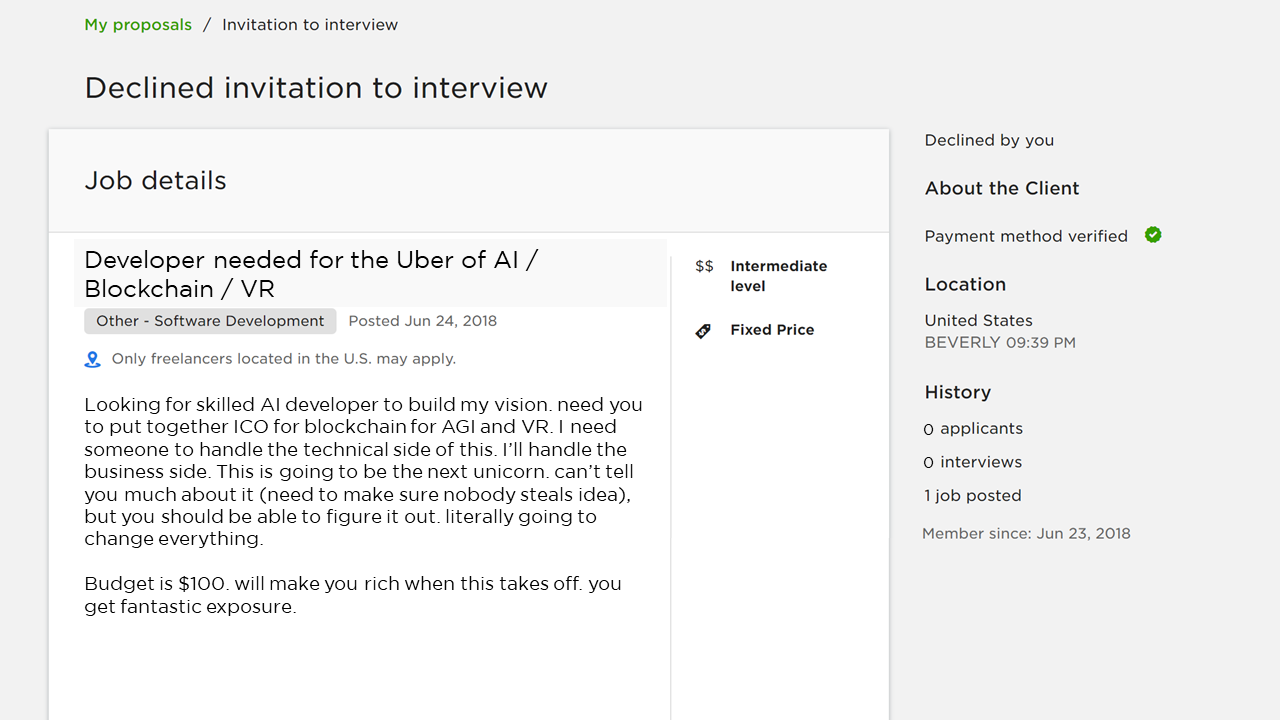

You

may have also built up a neat portfolio geared towards the ML subfield

you’re interested in. This portfolio solves one problem with places

hiring “junior” machine learning developers, but another remains. Few

people/organizations are looking for anything other than “Senior” ML

developers. I’ve seen job postings that require +5 years of experience

with libraries like Tensorflow, despite the fact that Tensorflow has only been out for 3 years.

Why does this happen? Most places that are hiring for ML work,

regardless of specifics of the job description, are pretty much looking

for the same thing: a Machine Learning Mary Poppins to come in and solve

all their problems.

To

increase your chances of convincing an organization you’re the solution

to their problems, it helps to build up a track record of successful

projects. In my case, I met with my first clients in person and agreed

on a project with them first, before the payment and contract was set up

on Upwork. The advantage of this method is that if your first client is

someone you know, you can get a starting reputation on the site, and

potentially get some constructive criticism at the same time.

The

work you DO end up getting may be slightly different from the goals you

had in mind when creating your portfolio. With that, your goal may have

been to demonstrate that you could code well, or implement a research

paper in code, or do a cool project. Freelance clients will only care

about one thing: Can you use ML to solve their problems.

They

say it’s better to learn from the mistakes of others instead of just

relying on your own. You can find such freelancing horror stories

curated at Clients From Hell.

While most of these examples are from freelance artists, designers, and

web developers, you may encounter some similar types (e.g., poor

communicators, clients who overestimate the capabilities of even

state-of-the-art machine learning, people with tiny or even nonexistent

budgets, and even the occasional racist).

While

it’s amusing to poke fun at some of the more extreme cases, it’s also

important to hold yourself to a high standard when it comes to working

for your clients. If your client is proposing something that is not

possible with the current state of ML as a field, do not try and prey on

their ignorance (that WILL come back to bite you). For example, I had

one client reach out to me about original content summarization, and how

they wanted to integrate it into their project. After doing some

research, I presented them with the performance results of some of

Google Brain’s summarization experiments. I told them that even with the

resources of Google, these results were still far below human

performance on summarization, and that I could not guarantee better

performance than the world’s state of the art. The interviewer thanked

me for my honesty. Obviously I did not get that particular contract, but

if I had lied and said that it was possible, then I would have been

faced with an impossible task, that likely would have resulted in an

incomplete project (and it would have taken a long time to get that

stain off my reputation). When it comes to expectations, be absolutely

transparent.

They say that trust has a half-life of 6 weeks. This actually is false. This applies when you are working in an office environment, but if you’re doing remote work, trust can have a much shorter half life. Think 6 days instead of 6 weeks.

Over

time, as you get new clients and grow your reputation, you will be able

to earn more as a freelancer and transition to more and more

interesting projects.

At

some point, however, you may decide that you prefer something with more

stability. This is a conclusion I eventually came to, even after

working with a company like Google as a contractor (the very first

machine learning contractor that the Tensorflow team ever hired). When I

did, I decided to take the leap to interview for full-time machine

learning engineer positions.

Part 10: Interviewing for Full-time Machine Learning Engineer Positions

This

is by far the most intense part of the machine learning journey.

Interviewing with companies is often much more intense than interviewing

with individual freelance clients (though most companies that hire

freelancers will do pretty thorough interviews for contract work as

well). If you’re interviewing with smaller startups, then they may be

much more flexible with their hiring process (compared to companies like

Facebook or Amazon, where an entire sub-industry has sprang up around

teaching people how to interview for those). Regardless of who you’re

interviewing with, just remember the following general steps.

The

first step is to to come up with a compelling “why”, as in what do you

want. Take time to reflect on your own thoughts and motivations. This

will allow you to focus on what you are looking for, and will probably

help you with answering questions about what you’re looking for.

The

next phase is to put together a study plan for your interview. I would

plan for about 3 to 6 months of studying the subjects from earlier in

this post. This assumes you’ve already put together some kind of

portfolio from either projects, or doing freelance work. For this phase,

you should spend at least 2 hours per day studying algorithms and data

structures, as well as additional time for reviewing the requisite math,

machine learning concepts, and statistics. Put together flashcards for

important concepts, but make sure to combine it with solving actual

coding problems.

Make

sure you put together a resume and portfolio. The resume should be one

page. You can follow the steps from earlier to put together your

portfolio. Once your resume is together, you can start reaching out to

companies.

Sites like Angel.co and VentureLoop can provide listings of openings available at startups. Y Combinator also has a page with job listings for their companies.

Don’t feel like you just need to rely on these listing sites. Ask

friends on social media if they’re aware of companies looking for

machine learning engineers, or perhaps even ask if they know about

specific companies. You can also find technical recruiters for specific