https://khanna.cc/blog/structuring-deep-learning-projects/

You want to train a deep neural network. You have the data. It’s labeled and wrangled into a useful format. What do you do now?

When I have a deep learning project, I follow these six steps.

Step 1. Pick a cost function.

Step 2. Pick an initial network architecture.

Step 3. Fit the training set well on the cost function.

Step 4. Fit the validation set well on the cost function.

Step 5. Verify performance on a test set.

Step 6. Verify performance in the real world.

Step 1. Pick a Cost Function

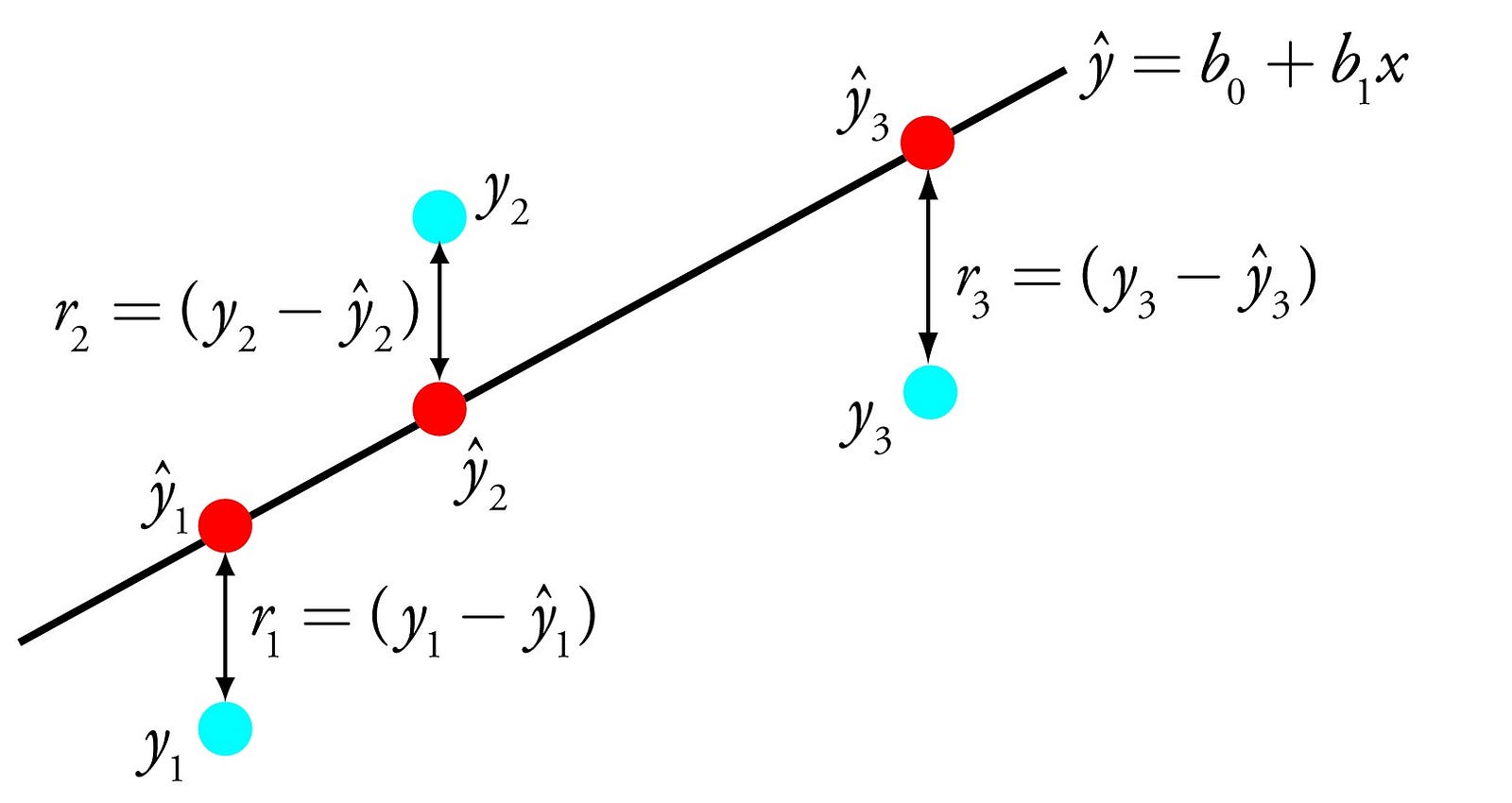

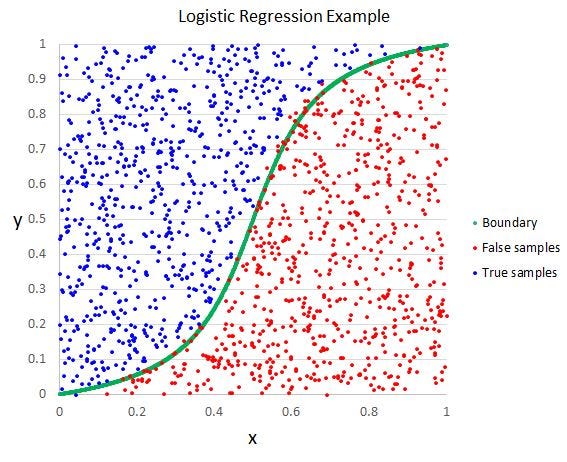

The appropriate cost function depends on the type of problem I’m

trying to solve. If I’m predicting an output value given an input value,

i.e., a regression problem, I use

mean squared error (MSE) loss. If I’m solving a classification problem with more than two classes, use

cross-entropy loss. If there are only two classes, I use

binary cross-entropy loss. These standard loss functions are available in all major deep learning frameworks.

If I have an unusual problem, such as

One-Shot Learning, I may need to design and use a custom loss function.

Step 2. Pick an Initial Network Architecture

For

structured learning problems

like predicting sales, I’ve found one, fully-connected hidden layer to

be a good starting place. The number of activations in that layer should

be between the number of input neurons and the number of output

neurons. The midpoint between the two usually isn’t a bad choice.

I’ve also seen the following formula, which is fine as a starting point.

Nh=Ns(a(Ni+No))

Ni

= number of input neurons

No = number of output neurons

Ns = number of samples in the training set

a = an arbitrary scaling factor between 2 and 10

If I’m doing computer vision, the best place to start is one of the proven architectures like

ResNet.

Step 3. Fit the Training Set Well on the Cost Function

The most important hyperparameter in fitting the training set is the learning rate (

α

). I don’t bother with trial-and-error and instead use a

learning rate finder that I adapted from the

fastai library. The learning rate finder outputs a plot that looks like this:

I choose a learning rate where the loss is still clearly decreasing. I

tend to pick a point that is a little bit to the right of the steepest

point in the plot, i.e., where the loss is still strongly decreasing and

has not yet been minimized. In the above plot, I would choose a

learning rate of

10−4

.

If the model is training very slowly or not very well, I replace the initial

stochasic gradient descent optimization algorithm with

Adam optimization.

If the model still isn’t properly fitting the training set, I’ll add learning rate decay.

Learning rate decay is reported to have been tried a few different

ways: exponential decay, discrete “staircase” decay, and even manual

approaches where the experimenter will visually observe when the loss

stops decreasing and reduces

α

accordingly.

I prefer to use a cosine-shaped learning rate decay, which decays

α

over the course of an epoch

in the shape of a cosine curve. This makes the rate of decay slowest at

the beginning and end of the epoch and highest in the middle of the

epoch.

I’ll usually also add “restarts” which

restarts the learning rate at it’s non-decayed value at the beginning of each epoch (or some integer multiple of epochs).

If I’m using some form of

transfer learning, I’ll try unfreezing the earlier layers of the neural network and training it with

differential learning rates.

At this point, if I’m still having trouble fitting the training set, I

have a few more hyperparameters I’ll tune either sequentially or by

random selection in the hyperparameter space.

- number of units in hidden layer

- minibatch size, in powers of 2: 64, 128, 256, 512. Rarely, 1024.

- number of hidden layers

I don’t bother tuning

β1

,

β2 or

ϵ for the Adam optimizer, since it doesn’t seem to make much difference.

If, after all this, I still cannot fit the training data well on the

cost function, I consider whether the overall objective should be

refined. The training inputs simply may not have the right information

to predict the output I’m trying to fit.

A good example of this is trying to predict a stock’s future price

based solely on that stock’s historical prices. If a stock’s movement is

purely a stochastic process as it relates to its historical price, I’m

not surprised when I can’t predict it’s future price with a deep neural

network.

Step 4. Fit the Validation Set Well on Cost Function

This is the step where I mainly spend my time. Getting a deep neural

network to generalize well to a validation set is often the most

difficult part of the project. Your deep neural network at this point

almost assuredly performs better on the training set than it does on the

validation set. There is in other words at least some degree of

overfitting to the training set.

Here are the steps I take to reduce validation set loss.

Dropout

First, I’ll try applying

dropout, which randomly zeros-out activations in the training set during training with some probability

p

. There’s no great rule of thumb for how I set

p, but I’ll try a couple of things.

I’ll apply dropout before the last linear layer at

p=0.25

and I’ll run multiple experiments tuning dropout up to

p=0.50. If that doesn’t help, I’ll add dropout to earlier linear layers of the neural network with a similar range of

p=0.25 to

p=0.50.

Like I said, there isn’t a great rule of thumb here, so it ends up

being some experimentation and trial-and-error to determine which

combination of dropout probabilities in which layers is the most

effective at reducing validation loss.

Weight Decay / L2 Regularization

Second, I’ll add some form of weight decay, such as

L2 regularization.

This is a classic technique in machine learning that reduces

overfitting. It works by adding a term to the cost function that looks

like this:

λ2∑j=1nw2j

λ

= regularization hyperparameter

wj = feature

j in weight matrix

w

n = number of features in weight matrix

w

One of the causes of overfitting is large weights, and this form of

weight decay heavily penalizes large weights in the weight matrix. By

adding this term to the cost function, a gradient step change that

increases the size of the weights in the weight matrix must improve the

network more than the increased cost associated with larger weights. The

weight decay parameter

λ

is an important one that has to be tuned.

The third thing I’ll do to reduce overfitting is normalize the mean

and variance of the input features over the training set. That means the

average of input feature

x1

over all training examples

m should equal 0 and the standard deviation should be 1. Same with features

x2...xn.

In math terms, the vector

x(i)

containing all of the features

j for a single training example

i should be modified like this:

μ=1m∑i=1mx(i)x:=x−μ

μ

is a vector with size equal to the number of input features in a single training example.

x is a matrix of size

n by

m, where

n is the number of input features in a single training example and

m is the total number of training examples. The substraction operator in the second equation broadcasts the vector

μ such that that vector is subtracted from each of the columns of matrix

x.

The formula for normalizing the standard deviations should be familiar:

σ2=1m∑i=1m(x(i))2x:=xσ2

I want to reiterate that I normalize the mean and standard deviation for each feature over the

training set, not over the features for each sample in the training set. It seems obvious now, but that detail tripped me up initially.

Another important detail is that I keep track of the mean and

standard deviation of the inputs from my training set and use those

statistics to normalize the validation and test sets. In other words, I

don’t calculate a mean and standard deviation over the validation set or

test set data. Rather, I use the scaling factors from the training set

to scale my validation and test sets.

Batch Normalization

Batch normalization

is becoming an increasingly standard part of any deep neural network.

Whereas the previous technique normalized the input features, the batch

norm technique reduces overfitting by normalizing the mean and variances

of the

hidden layer activations.

Batch norm is done per-minibatch. Like the input feature

normalization, I use the mean and variances from the training set to

apply batch norm to the validation and test sets. But unlike input

feature normalization, batch norm is done per-minibatch and not over the

whole training set, so I actually use an exponentially weighted average

of the mean and variances from the training set.

That can be a little mind-bending, so I’ll say it another way. In

batch norm, the mean and variance is taken on an

activation-by-activation basis over the training samples in the

minibatch. Since that will yield as many means and variances as there

are minibatches, I then apply an exponentially weighted moving average

across the minibatches to obtain a final mean and variance to apply to

my validation and test sets.

More Training Data & Data Augmentation

In my experience, overfitting is probably best solved by adding more

data to the training set and continuing to train the network. Collecting

more data can be expensive and time-consuming, which is why it’s not at

the top of my list.

Another approach is to use data augmentation. Data augmentation is

the process of synthesizing data to increase the data available to train

the network. It is an excellent option in computer vision problems

where it can be done by adjusting the lighting, rotation, orientation,

or other visual characteristics of the image. In this way, for every

image, you could get five or more images from it by transforming it in

subtle ways. After all, if you’re trying to build a network that can

detect cars on the road, whether that car is oriented left or right, and

whether it is sunny or rainy, there is still a car in the photo.

Data augmention as applied to structured data or natural language processing has not really been studied.

Vanishing and Exploding Gradients

Often, I’ll encounter vanishing gradients or exploding gradients.

Vanishing gradients are where where the gradients become so vanishingly

small that the network does not learn well with gradient descent.

Exploding gradients are where the gradients become so large, they exceed

the capability of the computer to calculate.

A first pass at solving both the problem of exploding and vanishing

gradients is to initialize the weight matrices in a particular way:

so-called,

He initialization.

He initialization is characterized by initializing the weight matrix

W[l]

to a zero-mean gaussian distribution with a standard deviation of:

2l−1−−−−−√

Although I did not expect it, initializing the weights in this

particular way has profound effects on minimizing the likelihood of

vanishing or exploding gradients.

If I’m training a recurrent neural network for something like language processing, I’ll almost always default to using a

Long Short-Term Memory unit in my recurrent neural network, which also operates to reduce the likelihood of vanishing or exploding gradients.

Finally, a couple of notes about exploding gradients specifically. If I start to see

NaN

appear in my gradients, it’s likely that I have an exploding gradient

problem. A blunt but effective way of dealing with exploding gradients

is to use gradient clipping. Gradient clipping sets an upper bound on

the gradients. If the gradient exceeds a certain threshold, it is

“clipped” to the threshold value.

Neural Network Architecture Search

Sometimes, the tuning of these hyperparameters does not seem to make

much of a difference. No matter how we tune them, the training set loss

is still acceptably low, but the validation set loss is much higher. It

therefore often makes sense to take a hard look at the architecture of

the neural network. Too many features in the input can cause the network

to fit noise in the training set. Too many activations in the hidden

layers can do the same thing. So I tinker with the number of neurons in

the hidden layers, perhaps reducing them in one hidden layer but

increasing them in another hidden layer. Or I will increase or reduce

the number of hidden layers themselves.

This technique, like most of the techniques in reducing overfitting,

is a lot of trial-and-error. I often need to experiment with many

different architectures until I find one that works well.

If the neural network performs well on the training and validation

sets, I’m feeling pretty good about it. The main risk at this point is

that, in the process of optimizing the network and tuning the

hyperparameters, I’ve accidentally overfit my validation set.

When I fit the validation set to the cost function in Step 4, I

looked to the loss, F-score or some other optimizing metric with respect

to the validation set. In essence, I tuned the hyperparameters

specifically optimizing on the validation set. In that way, I may have

fit the hyperparameters (and therefore the neural network) to noise in

the validation set, and the network may generalize poorly to data it has

not yet seen.

So, in this step, I run the network on an as-yet-unseen test set to

confirm the same results I saw in the validation set. If the network

performs poorly on a test set, I increase the size of the validation

set, either by additional data or by data augmentation. I then repeat

Step 4 and fit the larger validation before coming back to this Step 5

to verify its performance on a test set.

Don’t tune your network’s hyperparameters with respect to the test

set loss! If you do, you’ll end up with a network overfit on your

training set, validation set

and test set and you won’t realize it.

Now the fun part! Make sure the network performs well in the real

world. If you’ve trained a cat classifer, start feeding the network

pictures of your cat. If you’ve trained a recurrent neural network

sentiment classifer for corporate press releases, feed it Microsoft’s

latest press releases and see how it does.

If the network performs poorly in the real world, but performs well

on the training, validation and test sets, something is wrong. You may

have overfit to your test set somehow. Change your validation and test

sets and see if the network still performs well on those. If it does,

and it still has issues performing in the real world, it may be time to

re-evaluate the cost function you are using (or your overall objective).

To be honest, I have not encountered this situation. In my

experience, if I successfully make it to this Step 6, the network does

not have issues in the real world.

Summary Checklist

Below is a short, checklist summary of the things to do or look out for in each step.

- Step 1. Cost Function

- Step 2. Initial Network Architecture

- Structured learning: one fully-connected layer with number of activations between input output layer sizes.

- Computer vision: start with ResNet.

- Step 3. Training Set

- Step 4. Validation Set

- Step 5. Test Set

- If there are issues, increase size of validation set and go back to Step 4.

- Step 6. Real World

- If issues, change validation and test sets and go back to step 4.

Acknowledgements

This post is inspired by my experiences in the

deeplearning.ai Coursera specialization as well as the

Practical Deep Learning for Coders course. Many thanks to Andrew Ng and Jeremy Howard for their hard work as educators.