Like

most devs, I have a diverse set of interests: functional programming,

operating systems, type systems, distributed systems, and data science.

That is why I was excited when I learned that Will Kurt, the author of Get Programming with Haskell, wrote

a a bayesian statistics book that is being published by No Starch

Press. There aren’t many people that write books on different topics. I

was sure that Will had something interesting to share in this new book. I

wasn’t disappointed. The book is an excellent introduction, specially

for those of us that have a rough time with advanced math but that want

to advance in the data science field. I recommend reading the book after

reading Think Stats, but before reading Bayesian Methods for Hackers,

Bayesian Analysis with Python and Doing Bayesian Data Analysis.

If you like the interview I recommend that you also read the interviews we did with Thomas Wiecki and Osvaldo Martin about Bayesian analysis and probabilistic programming.

Finally I wanted to thank two members of my team (Pablo Amoroso and Juan Bono) for helping me with the interview.

Reach me via twitter at @unbalancedparen if you have any comments or interview request for This is not a Monad tutorial.

If you have an idea, you are looking for a part time CTO, need a team of devs or have maintenance work ping us: LambdaClass.

1. Why a new statistics book?

Nearly

all of the many excellent books on Bayesian statistics out now assume

you are either familiar with statistics already or have a pretty solid

foundation in programming. Because of this the current state of Bayesian

statistics in often as an advanced alternative to classical (i.e.

frequentist) statistics. So even though Bayesian statistics is gaining a

lot of popularity, it’s mostly amount people who already have a

quantitative background.

When

someone wants to simply “learn statistics” they usually pick up an

introduction based on frequentist statistics and end up half

understanding a bunch of tests and rules, and feel very confused by the

subject. I wanted to write a book on Bayesian statistics that really

anyone could pick up and use to gain real intuitions for how to think

statistically and solve real problems using statistics. For me there’s

no reason why Bayesian statistics can’t be a beginners first

introduction to statistics.

I

would love it if, one day, when people said “statistics” it implied

Bayesian statistics and frequentist statistics was just an academic

niche. To get there we need more books that introduce statistics to a

wide audience using Bayesian methods and assume this may be the readers

first exposure to stats. I toyed with the idea of just calling this book

“Statistics the Fun Way”, but I know I would probably get angry emails

from people buying the book help with stats 101 and getting very

confused! Hopefully this book will be a small step in getting “stat 101”

to be taught from the Bayesian perspective, and statistics can make

sense from the beginning.

2. Who is your intended audience for the book? Could anyone without a math background pick it up?

My

goal with Bayesian Statistics the Fun Way was to create a book that

basically anyone with a high school math background could pick up and

read. Even if you only vaguely remember algebra, the book moves at a

pace that should be easy to follow. Bayesian statistics does require

just a little calculus and is a lot easier with a bit of code, so I’ve

included two appendices that cover enough R to work as an advanced

calculator and enough background in the ideas of calculus that when the

book needs talk about integrals you can understand. But I promise that

there is no solving of any calculus problems required.

While

I worked hard to limit the mathematical prerequisites for the book, as

you read through the book you should start picking up on mathematical

ways of thinking. If you really understand the math your using, you can

make better use of it. So I don’t try to shy away from any of the real

math, but rather work up to it slowly so that all the math seems obvious

as you develop your understanding. Like many people, I used to believe

that math was confusing and difficult to work with. In time I really saw

that when math is done right, it should be almost obvious. Confusion in

mathematics is usually just the result of moving too quickly, or

leaving out important steps in the reasoning.

3. Why should software developers learn probability and statistics?

I

really believe everyone should learn some probability and statistics

because it really does help to reason about the uncertain world which is

our everyday life. For software developers in particular there are few

common places that its useful to understand statistics. It’s pretty

likely that at some point in your career in software, you’ll need to

write code that makes some decision based on some uncertain measurement.

Maybe it’s measuring the conversion rate on a web page, generating some

random reward in a game, assigning users to groups randomly or even

reading information from an uncertain sensor. In all these cases really

understanding probability will be very helpful. In the software part of

my career I’ve also found that probability can help a lot in

troubleshooting bugs that are difficult to reproduce or to trace back to

a complex problem. If a bug appears to be caused by insufficient

memory, does adding more memory decrease the probability of the bug in a

meaningful way? If there are two explanations for a complex bug, which

should be investigated first? In all these cases probability can help.

And of course with the rise of Machine Learning and Data Science,

engineers are more and more likely to be working on software problems

that involve working directly with probabilities.

4. Could you give a brief summary of the difference between the frequentist and bayesian approaches to probability?

Frequentists

interpret probability as a statement about how frequently an event

should occur in repeated trials. So if we toss a coin twice we should

expect to get 1 head because the frequency of heads is 1/2. Bayesians

interpret probability as a statement of our knowledge, basically as a

continuous version of logic. The probability of getting heads in a coin

toss is 0.5 because I don’t believe getting heads is any more likely

than getting tails. For coin tosses both schools of thought work pretty

well. But when you talk about things like the probability that your

favorite football team will win the world cup, talking about degrees of

belief makes a lot more sense. This additionally means that Bayesian

statistics does not make statements about the world but about our

understanding of the world. And since we each understand the world a bit

differently, Bayesian statistics allows us to incorporate that

difference into our analysis. Bayesian analysis is, in many ways, the

science of changing your mind.

5. Why did you choose to focus on the bayesian approach?

There

are plenty of really great philosophical reasons to focus on Bayesian

statistics but for me there is a very practical reason: everything makes

sense. From a small set of relatively intuitive rules you can build out

the solutions to any problem you encounter. This gives Bayesian

statistics a lot of power and flexibility, and also makes it much easier

to learn. I think this is something programmers will really like about

Bayesian reasoning. You aren’t applying ad hoc tests to a problem, but

reasoning about your problem and coming up with a solution that makes

sense. Bayesian statistics is really reasoning. You agree to the

statistical analysis only when it genuinely makes sense and convinces

you, not because some seemingly arbitrary test result achieves some

equally arbitrary value. Bayesian statistics also allows us to disagree

quantitatively. It’s quite common in everyday life that two people will

see the same evidence and come to different conclusions. Bayesian

statistics allows us to model this disagreement in a formal way so that

we can see what evidence it would take to change our beliefs. You

shouldn’t believe the results of a paper because of a p-value, you

should believe them because the truly convince you.

6. How Bayesian Statistics Is Related To Machine Learning

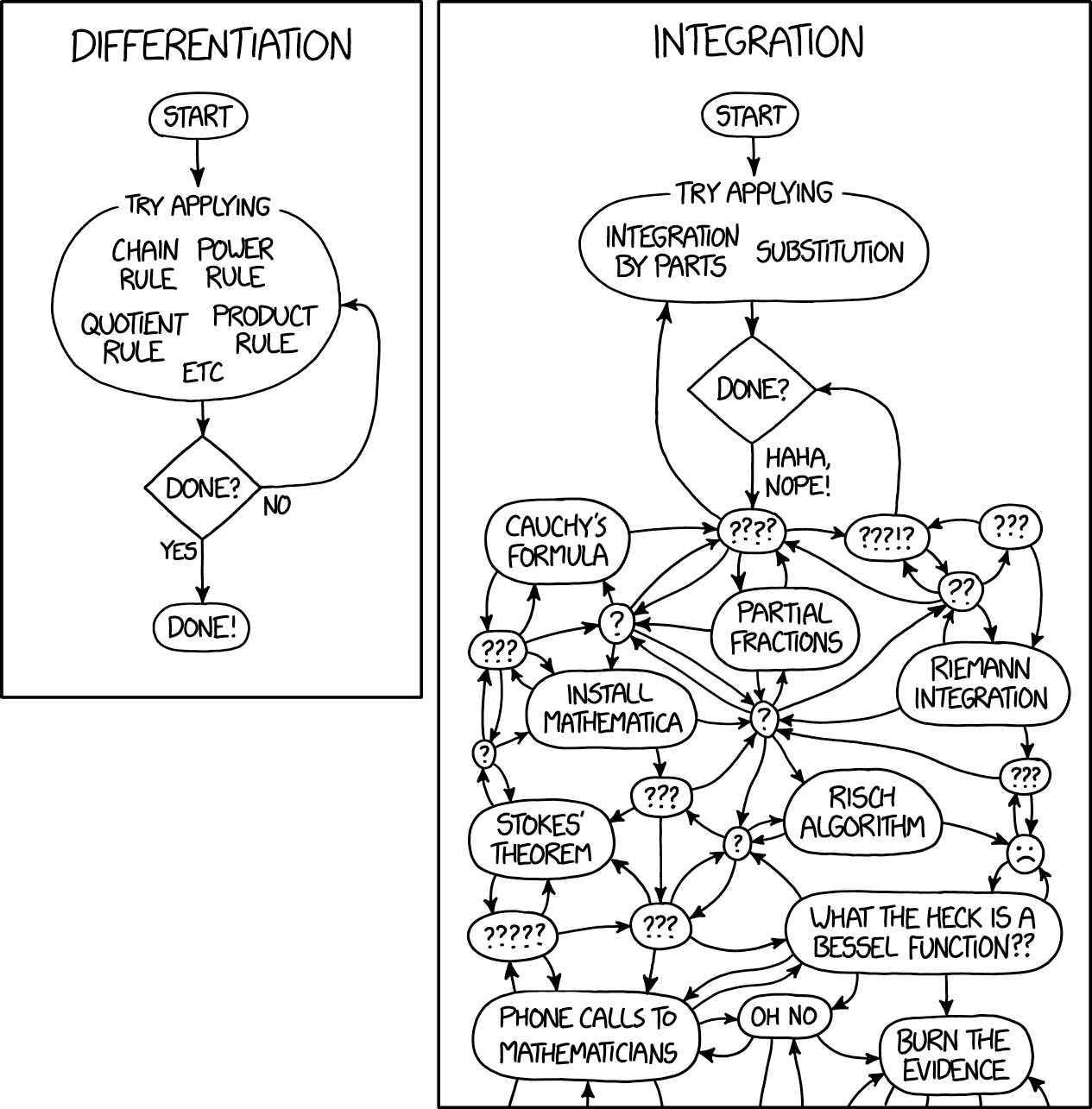

One

way I’ve been thinking about the relationship between Bayesian

Statistics and Machine Learning (especially neural networks) in the way

that each deal with the fact that calculus can get really, really hard.

Machine Learning is essentially understanding and solving really tricky

derivatives. You come up with a function and a loss for it, then compute

(automatically) the derivative and try to follow it until you get

optimal parameters. People often snarkily remark that backpropagation is

“just the chain rule”, but nearly all the really hard work in deep

learning is applying that successfully.

Bayesian

statistics is the other part of calculus, solving really tricky

integrals. The Stan developer Michael Betancourt made a great comment

that basically all Bayesian analysis is really computing expectations,

which is solving integrals. Bayesian analysis leaves you with a

posterior distribution but you can’t use a distribution for anything

unless you integrate over it to get a concrete answer. Thankfully no one

makes snarky comments about integrals because everyone knows that it

can be really tricky in the simplest case. This xkcd makes that point

nicely:

So

in this strange way the current state Machine Learning and Bayesian

Statistics are what happens when you push basic calculus ideas to the

limits of what we can compute.

This

relationship also outlines the key differences. When you think about

derivatives you’re looking for a specific point related to a function.

If you know location and time, the derivative is speed and can tell you

when you went the fastest. Moving the needle in ML is getting a single

metric better than anyone else. Integration is about summarizing an

entire process. Again if you know location and time, the integral is

distance and tells you how far you’ve traveled. Bayesian statistics is

about summarizing all of your knowledge about a problem, but this allows

us to not just give single predictions but also say how confident we

are in a wide range of predictions. Advancement in Bayesian statistics

is about understanding more complex systems of information.

7.

If your readers wanted to dig deeper into the subject of the book,

where would you point them to (books, courses, blog posts, etc)?

The

biggest inspiration for this book was E.T. Jaynes’ “Probability Theory:

the Logic of Science”. My secret hope is that “Bayesian Statistics the

Fun Way” can be a version of that book accessible to everyone. Jaynes’

book is really quite challenging to work through and is presents a

pretty radical version of Bayesian statistics. Aubrey Clayton has done

an amazing service by putting together a series of lectures on the key chapters of this book.

And of course if you liked reading the book you’d probably enjoy my blog.

I haven’t been posting much recently since I’ve been writing a

“Bayesian Statistics the Fun Way” and before that “Get Programming with

Haskell” but I’ve got a ton of posts in my head that I really want to

get down on paper soon. Generally the blog, despite the name, is not

strictly Bayesian. Typically if I have some statistics/probability topic

that I’m thinking about, it will get fleshed out into a blog post.

8. In your experience, what is a concept from probability/statistics that non experts find difficult to understand?

Honestly,

the hardest part is interpreting probabilities. People really lost

faith in a lot of Bayesian analysts like Nate Silver (and many others)

when they were predicting 80% or so chance that Clinton would win the

2016 election and she didn’t. People felt like they had been tricked and

everyone was wrong, but 80% chance really isn’t that high. If my doctor

tells me I have an 80% chance to live I’m going to be really nervous.

A

common approach to this problem is to point to probabilities themselves

and say that they are a poor way to express uncertainty. The fix then

is that you should be using odds or likelihood ratios or some

decibel-like system similar to Jaynes’s idea of evidence. But after

really thinking about probability for along time I haven’t found that

there’s a universally good way to express uncertainty.

The

heart of the problem is that, deep down, we really want to believe that

the world is certain. Even among experienced probabilists there’s this

persistent nagging feeling that maybe if you do the right analysis,

learn the right prior, add another layer into your hierarchical model

you can get it right and remove or at least dramatically reduce

uncertainty. Part of what draws me to probability is the weird mixture

of trying to make sense of the world and the mediation on the fact that

even when trying your hardest, the world will surprise you.

9.

What are your thoughts on p-values as a measure of statistical

significance? Could you give us a brief description of p-hacking?

There’s

two things wrong with p-values. First of all, p-values are not the way

sane people answer questions. Imagine how this conversation would sound

at work:

Manager: “Did you fix that bug assigned to you?”

You: “Well I’m pretty sure I didn’t not fix it…”

Manager: “If you fixed it, just mark it fixed.”

You: “Oh no, I really can’t say that I fixed it…”

Manager: “So you want to mark it ‘will not fix’?”

You: “No, no, I’m pretty sure that’s not the case”

p-values

confuse people because they are, quite literally, confusing. Bayesian

statistics gives you a posterior probability, which is exactly the

positive answer to the question being posed that you want. In the

previous dialog the Bayesian says “I’m pretty sure it’s fixed”, if the

manager wants you to be more sure, you collect more data and then you

can say “I’m basically certain it’s fixed”.

The

second problem is the culture of arbitrarily picking 0.05 as some magic

value that has meaning. Related to the previous question about

understanding probabilities, a 5% chance of something occuring does not

make it very rare. Rolling a 20 sided die and getting a 20 has a 5%

chance, and anyone who knows of Dungeons and Dragons (D&D) knows

that this is far from impossible. Outside of role playing games,

focusing on a die roll is not a great system of verifying true from

false.

And

that brings us to p-hacking. Imagine you’re playing D&D with some

friends and you role twenty 20-sided dice all at one. You then point one

that landed on 20 and proclaim “that was the die I meant to roll, the

rest are all just test dice.” It’s still cheating even if you

technically did roll a 20. That’s what p-hacking essentially is. You

keep doing analysis until you find something that is ‘significant’, and

then claim that’s what you were looking for the entire time.

10. Any closing recommendations on what book to read next after reading your book?

Now

that I’ve finished writing this book I finally have time to start

catching up on other books that I didn’t have time to read while writing

it! I’m really enjoying Osvaldo Martin’s “Bayesian Analysis with

Python” (I know Not Monad Tutorial interviewed him not long ago). It’s a

great book that approaches Bayesian analysis through PyMC3. I really

think the world of probabilistic programming is very exciting and will

be more and more an essential part of practical Bayesian statistics.

Another book I really want to read is Richard McElreath’s “Statistical

Rethinking”. It has a second edition coming out soon so I’m slightly

hesitant to get copy before that. McElreath has put up a bunch of great

supporting material on his website,

so I might not be able to wait until the 2nd edition to get a copy.

Both of these sources would be great next steps following “Bayesian

Statistics the Fun Way”. Another good recommendations would be

Kruschke’s “Doing Bayesian Data Analysis”.

No comments:

Post a Comment